Incredible to us in our days of satellite imagery, half a millennium ago maps were rarely accurate and often based on less than fact. One such historical inaccuracy, which is discussed in the article, is the bay now called Dollart and the myth of the Atlantis of the Clay.

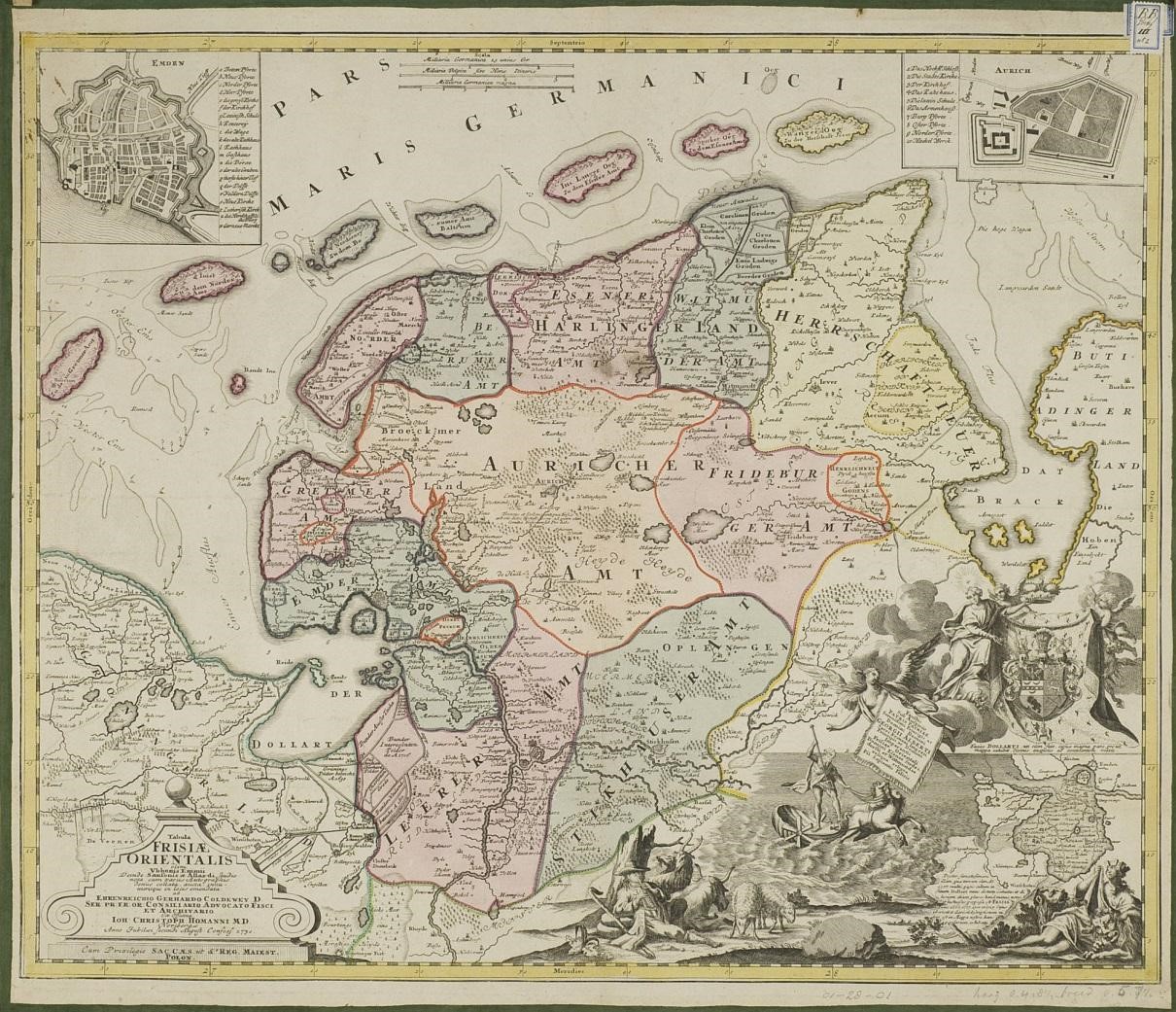

Sixteenth-century maps showed, correctly, the Dollart, an inlet that formed the west coast of East Frisia (Frisiea Orientalis). Today, the water is so shallow as to reveal the mud at low tide. Many early cartographers included an inset, showing the area of the bay as a lowland dotted with villages. The insets were labeled “the Reiderland,” and indicated a flood which occurred in the year 1277. The information was based on a 1574 map by Jacob Vermeersch.

“[Ubbo Emmius] criticized [established cartographers] for affording local folklore a credibility that it did not merit.” Emmius omitted the deluge in his 1616 map of the area, discounting fables and legends, preferring to rely on primary sources.

According to the myth of the Atlantis of the Clay, the Reiderland was submerged beneath the sea due to the transgressions of its inhabitants. We have discovered since that, while the land did indeed suffer inundation, the flood occurred in 1509—only 65 years before the first map showing it to have been three hundred years prior.

What caught my eye was Emmius’s 1730 (posthumous) map. We see the Reiderland flood inset (lower right), added by the publisher after the cartographer’s death in 1625. We note, as well, nicely delineated borders dividing a landmass surrounded by an island-strewn sea. We remark additional insets in the upper corners: one a city (left), the other a fortress (right). When we identify these two, respectively, as base town and ruined castle, the historical map transforms into something more magic. That is, a map depicting an area we may explore in a fantasy adventure campaign.

When we identify these two, respectively, as base town and ruined castle, the historical map transforms into something more magic.

While the date is incorrect, and the flood’s cause may have more to do with nature’s whim than human foible, still, the Reiderland’s 33 villages lie beneath the silt of the tidal flat in this Atlantis of the Clay.

Pingback: Monstrous Denizens of the Pale Moor – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: Thirteen Graves – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: Base Town Emden – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: Hekselannen – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: Encounters in the Hex Lands – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: A Forsaken Peninsula – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: Beyond the Pale – DONJON LANDS

Pingback: Warlock of the Pale Moor – DONJON LANDS