The Sign of the Oneiromancer

Urgent cries in distant dark. Dying echoes, fading into empty space. A spark—a flash of light, flickering orange. Columns rise high above, stabbing gloomy shade. Tunnels twisting out of sight.

Stumbling, lost, behind lumbering figures, purple-cloaked. Under arch, stepping down. Between close walls, beneath heavy vault, cauldrons crouch on red coals. Chanting priests raise green goblets to a shadowed image. All eyes are closed…

Many are troubled by such nightmares. Some wake, seeking respite. Some lie yet in fitful sleep. Those who talk about them report the nightmares always end with a vision of the Sign of the Oneiromancer.

—Boxed text reprised from “Dreaming Amon-Gorloth.”

The Sign of the Oneiromancer

A glyph in the form of two diamonds, one inside the other, marks the entrance to this public house. Until recently, it was a quiet establishment, doing enough business but not over crowded. Since the nightmares began, townsfolk come here, seeking solace. They share their dreams and quench their fears in barley beer. Some stay through the night, when they can’t bear to surrender consciousness to the horror.

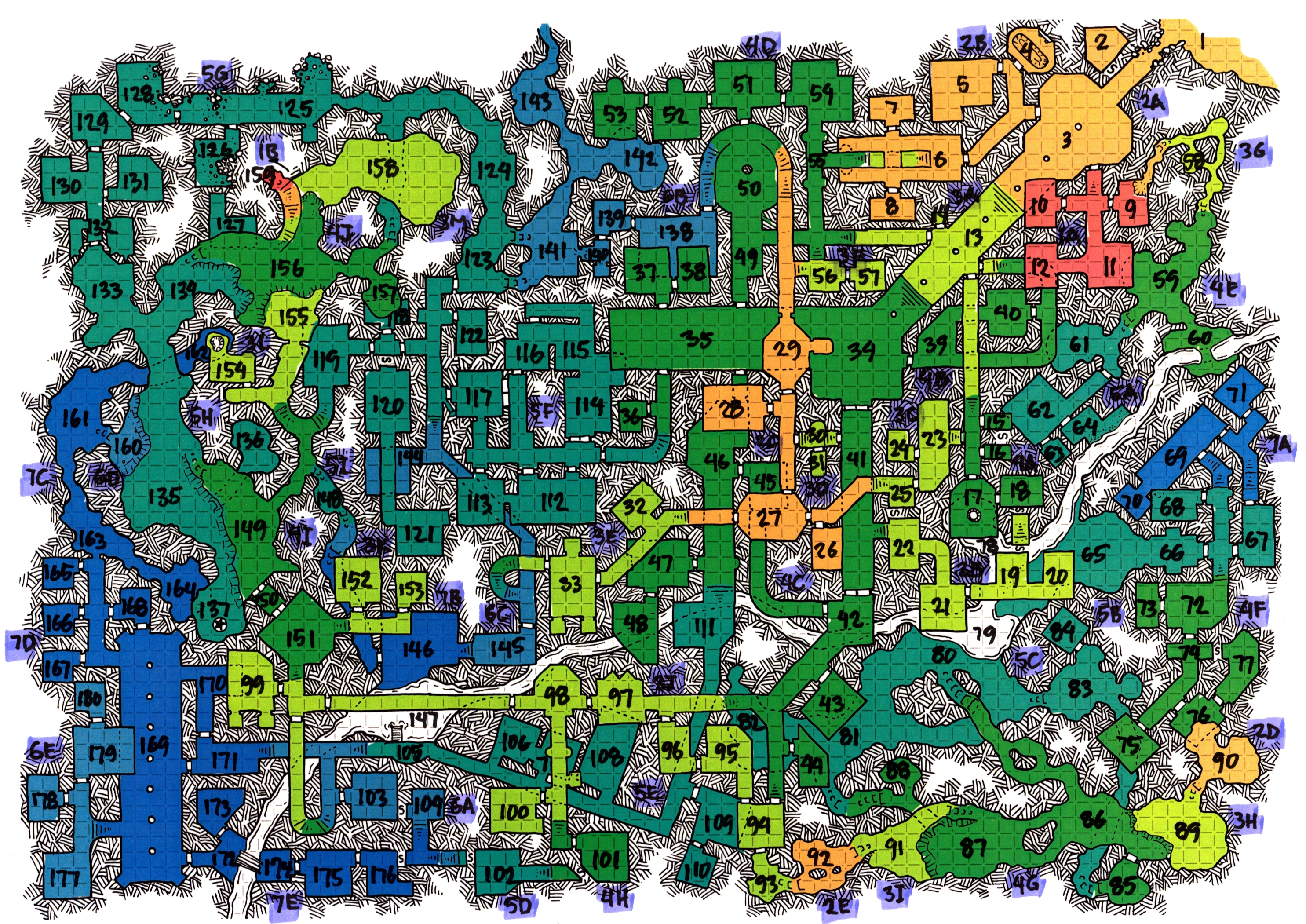

The Sign of the Oneiromancer is an inn, where adventurers can rest between expeditions. In its upper rooms, characters may sleep in relative comfort and safety. In its ground floor entertainment hall, they may restore themselves, meet prospective hirelings, and gather and spread rumors, true or false, about the nearby dungeon.

Oil lamps cast a yellow glow in the long, low hall. Wooden rafters support mud brick construction. Plaster walls bare painted scenes of the Solar Goddess on one side and the Sun King on the other. The warm, still air is filled with scents of citrus and flowers and fresh baked bread.

Patrons crowd around low tables, sitting on floor cushions. Some, in pairs or groups, play games: senet, mehen, and hounds and jackals.

Others share a meal. They eat with their fingers: grilled fowl, glistening with grease, roasted vegetables and green scallions, and date cakes drenched in honey. With long knives, they cut thick slices from hot loaves of wheat bread. They drink beer from ceramic cups and talk in subdued tones and close whispers.

At the hall’s far end, a harpist plucks a languid tune. A trio of dancers bestows lily flower collars to new comers and offers a dance in exchange for coin.

Background

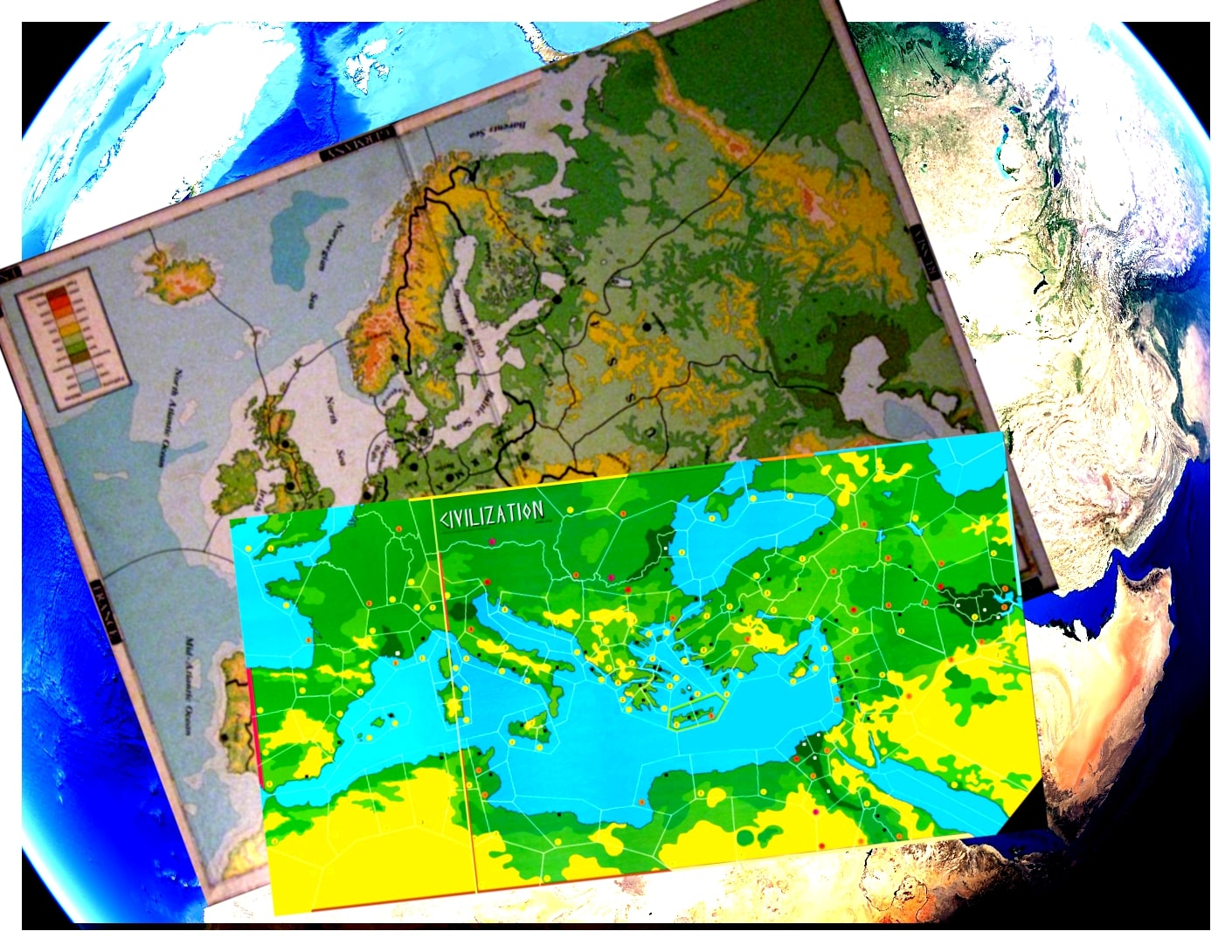

At campaign start, player characters who live in town, or who have spent a night there, are troubled by the nightmares. All PCs are familiar with the Myth of Amon-Gorloth, and they are aware of the following legend. In addition, each PC might begin play knowing one rumor from the table below. Otherwise, rumors may be learned through interaction with townsfolk.

Legend of the Dreaming Priests

Long ago, evil cultists, called the “dreaming priests,” built a dungeon in the Shunned Cairns. The dungeon is known as the Deep Halls, and within its depths, they sought to revive a long dead god, until the Sun King’s Radiant Host destroyed the cult. Details of the story are lost to history, for to talk about the priests is to wake them from dream.

Rumors

The following rumors circulate in town and especially at the Sign of the Oneiromancer. Some of them are true.

| Rumor Table (d12) | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Some folks don’t talk about it, but everyone in town is having these dark dreams. |

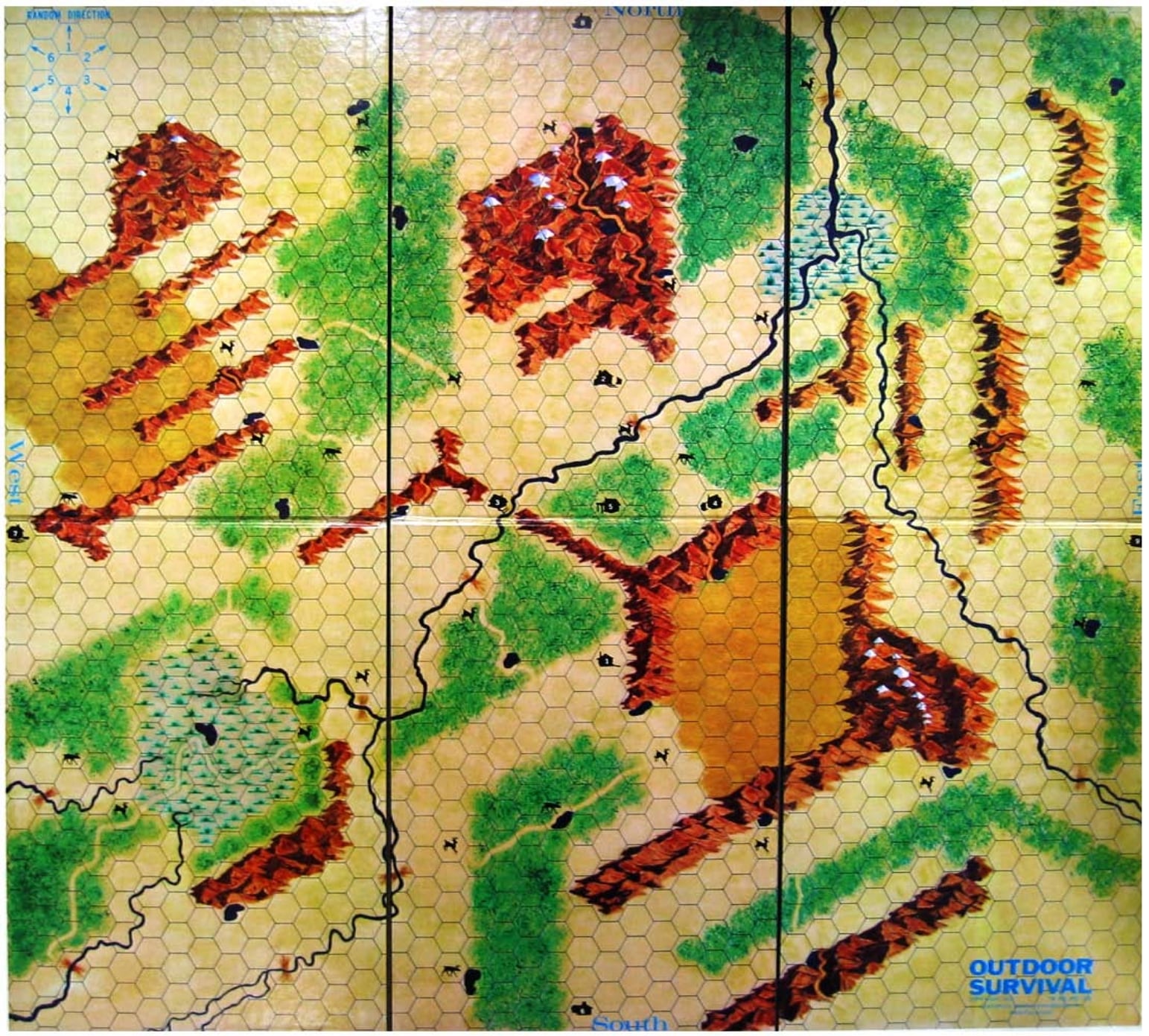

| 2. | An old track leading northwest into the Shunned Cairns goes to the Deep Halls. |

| 3. | The Deep Halls are like a maze: once you get in, you can’t get out. |

| 4. | Getting out of the Deep Halls is easy; just keep right. |

| 5. | The Radiant Host vanquished the dreaming priests in a war a hundred years ago. |

| 6. | Since the war, it is forbidden by the Sun King’s decree to enter the Shunned Cairns. |

| 7. | Now the dreaming priests have come back as walking dead. |

| 8. | In the Deep Halls, the ever-flowing waters of a fountain shrine to the Solar Goddess heal the wounded and cure the sick. |

| 9. | Demi-humans are known to traverse the Shunned Cairns. |

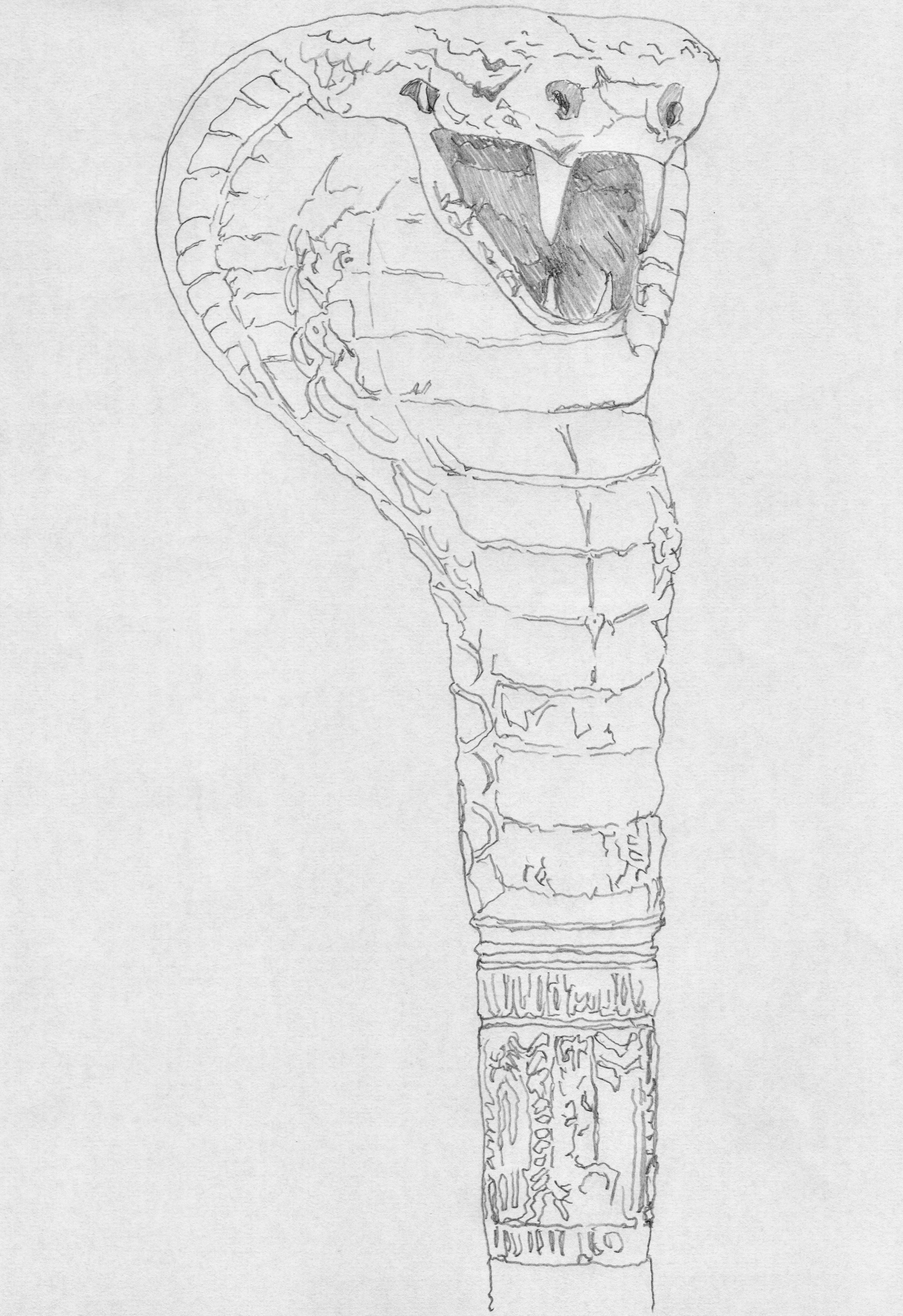

| 10. | A dreaming priest once wielded a powerful magic staff, but after he was defeated, the staff was never found. |

| 11. | An old hag, hunched and grumbling, is sometimes seen hobbling along the streets at night on a cane. |

| 12. | Outlaws in the Shunned Cairns waylay travelers and raid unguarded sites. |

![Single Dice Roll [Traditional] Single Dice Roll [Traditional]](https://www.donjonlands.com/wp-content/uploads/_images/legacy/6a00d8342106f153ef02942f905f3b200c.jpg)