Using How to Host a Dungeon for #Dungeon23

“Not playing through it, I use the rules booklet as a reference work. Tony Dowler’s dungeon-building game provides primordial nexuses, ancient civilizations, and master villains to fill out the dungeon’s space and history should need arise.”

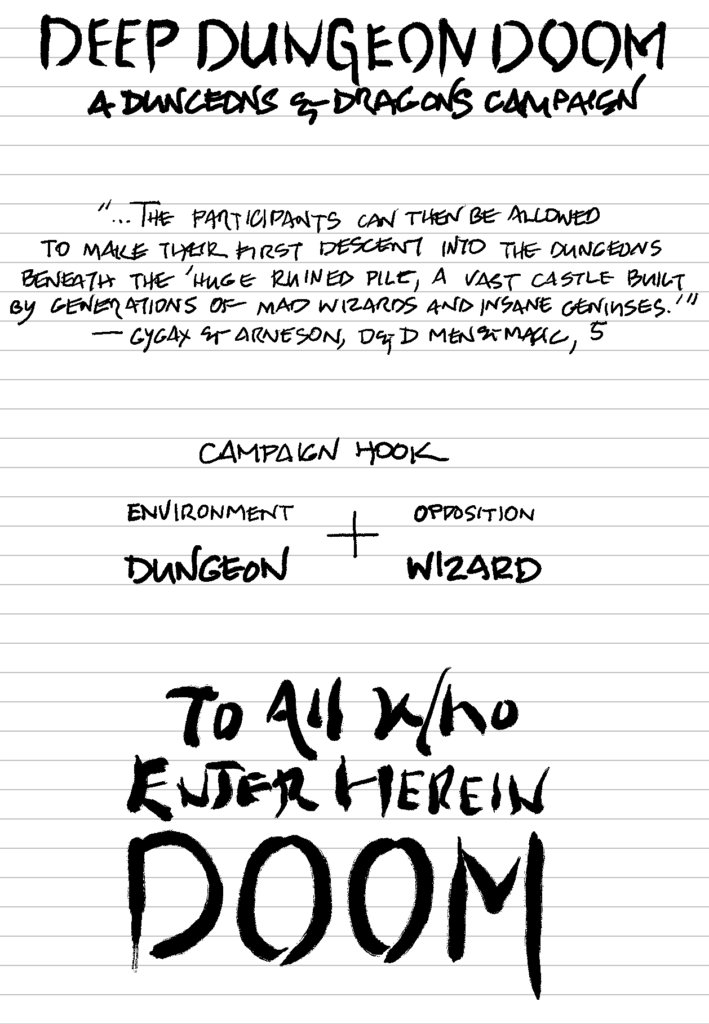

—on How to Host a Dungeon, Inspiration, “Campaign Hook: ‘To All Who Enterin—DOOM’”

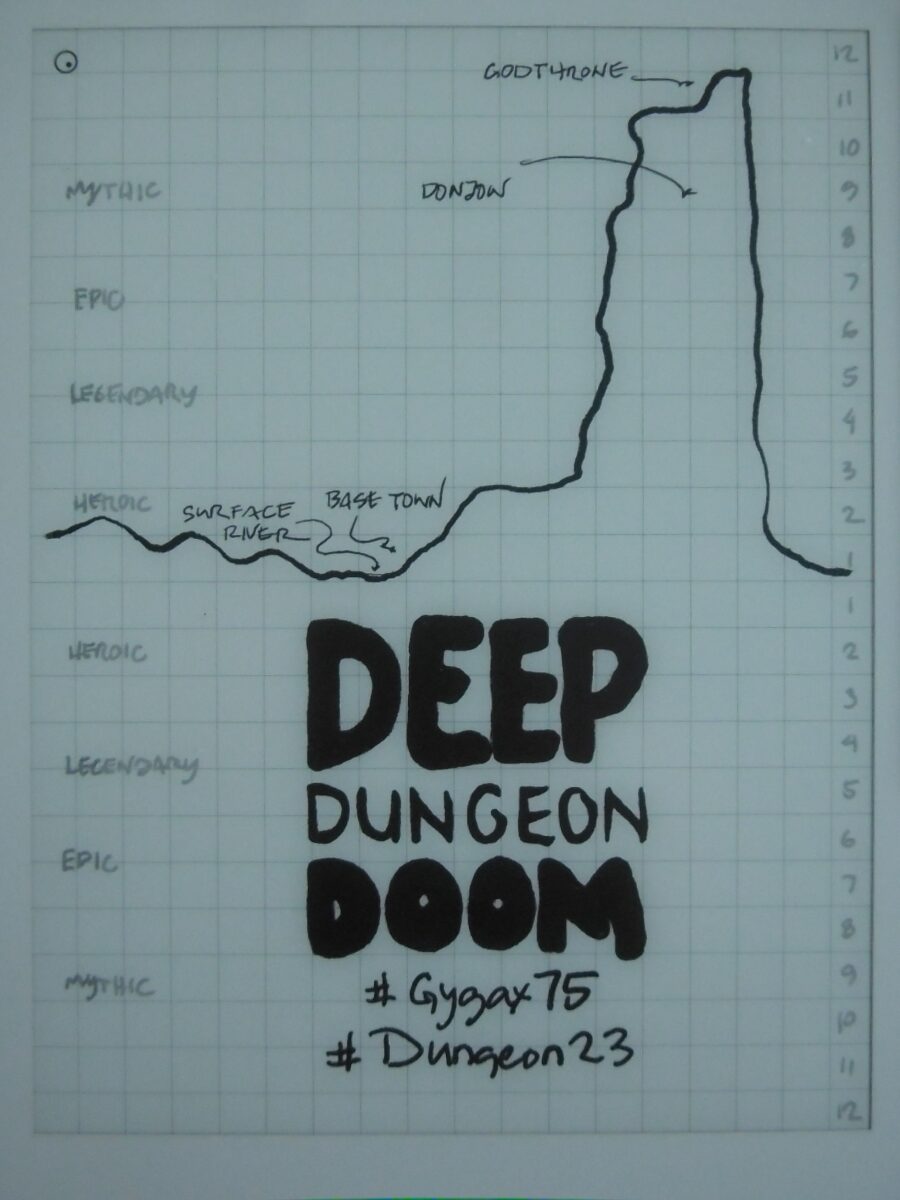

As a prelude to some future rendition of Deep Dungeon Doom, I’ll play through an extravagant run of How to Host a Dungeon to establish a robust and detailed history for the 24-level adventure locale. By extravagant, I mean: instead of eight, the dungeon spans 24 strata; not one but a few nexus points are planted within; instead of one each, I’ll run several ages of civilization, monsters, and villainy. Even greater in scope than Wyrm Dawn, it’s a dream project for another day.

Meanwhile, for this outing, we adhere to #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23’s prime directive: “Don’t overthink it!” How to Host a Dungeon is a reference work. I use elements from the game’s various “ages” as focal points. So, “rooms” that might be built during civilization and villainous periods become sections of the dungeon, principle characters become major historical figures, and a brief outline of history based on the successive ages becomes the framework for hanging past events on a time line.

“The (unobserved) past, like the future, is indefinite and exists only as a spectrum of possibilities.”

—Stephen Hawking & Leonard Mlodinow, The Grand Design

Working Framework for Historical Events in Deep Dungeon Doom

The following table outlines the major historical periods in the dungeon. This is how I see the time line now. Other—perhaps many other—civilizations, monster ages, and villainous periods, certain to have taken place, may be inserted as the campaign progresses. A thing is malleable until it is observed, that is, used in play.

Time Line—Deep Dungeon Doom

| Ages | Primordial Nexuses | Civilizations | Villains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prehistory | |||

| Void | |||

| Primordial Monsters | |||

| Alien (Illmind) | |||

| Cyclopean Complex | |||

| Godthrone | |||

| Gateway (Abyss) | |||

| Demon | |||

| Devil (empire) | |||

| Bronze Age | |||

| Drow | |||

| Iron Age | |||

| Dwarven | |||

| Giant (empire) | |||

| Dark Age | |||

| Medieval Age | |||

| Magician (Lore Kings) | |||

| Fearthoht (empire) | |||

| [Present] | ? |

This historical framework is mostly for the DM, so to maintain some coherence as I build out dungeon areas. The process also informs the present situation in the dungeon. Player characters might learn some of the dungeon’s history as they explore it, but they are not obliged to. Players themselves may not much care.

Illmind

The Illmind is a sinister collective of hyperintelligent, extra-dimensional beings. It is responsible for the Rending—the cosmic cataclysm that is the campaign world’s origin. (See Song of the World Dragon.) After the cataclysm, the Illmind established a colony at this location. The colony, whose objective is not yet known to me, grew into the dungeon’s first civilization.

The Illmind civilization ends with the construction of the Godthrone (Megastructure) and the Gateway (Uplift Facility). The latter gates in demons to destroy alien works. The former is now called “Godthrone,” but its true purpose is unknown.

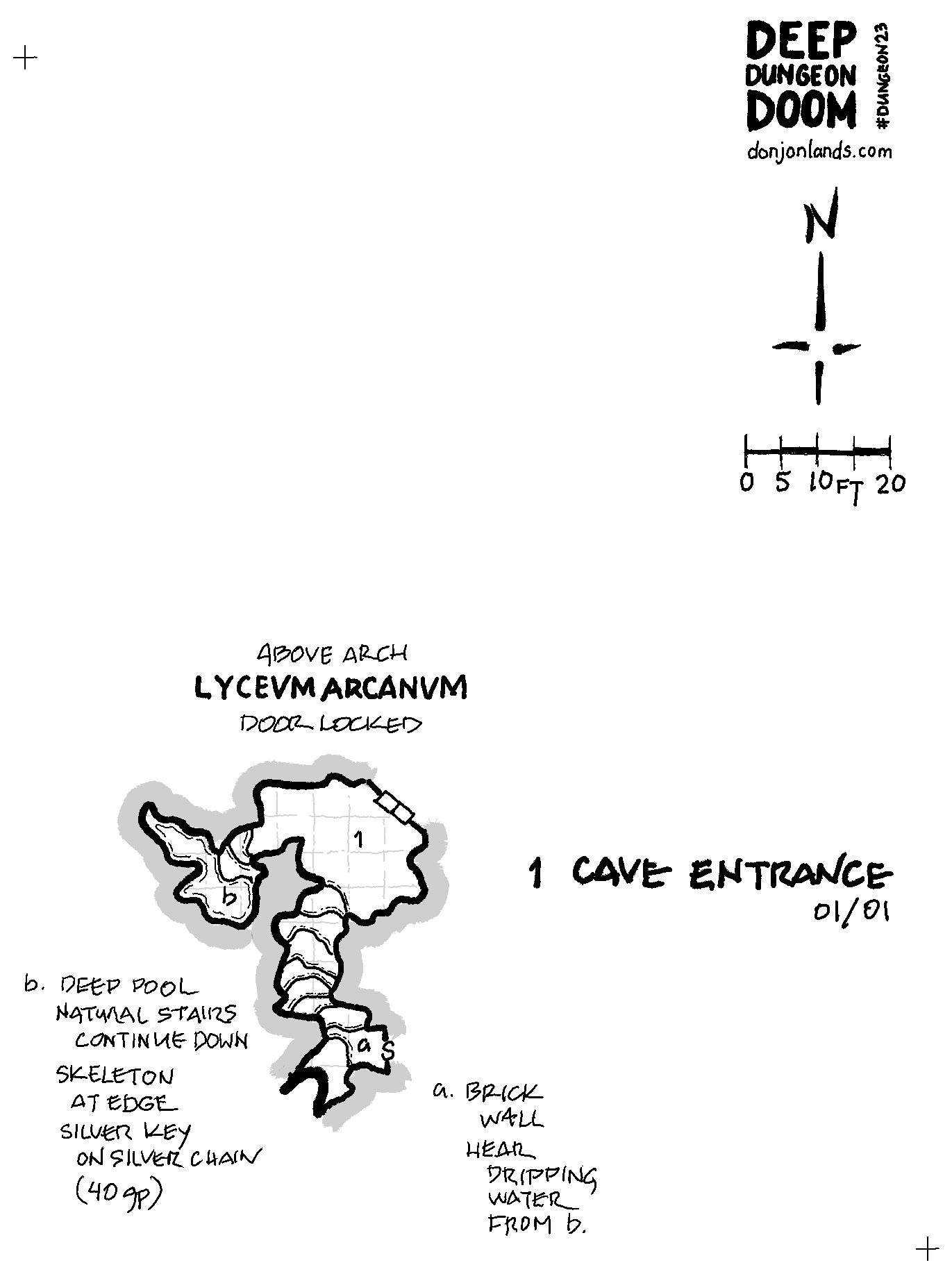

Lyceum Arcanum

To get straight into the thick of things, I want to start the campaign with something about the wizards. Looking at the magician civilization’s constructions, I am attracted to “Lyceum Arcanum.” According to How to Host a Dungeon1, this large structure is built at a nexus point either above or below ground (16). I place it on the surface, knowing that, at civilization’s end, it is buried under a new surface level. For the required nexus, I choose Ley Lines, which is one attraction for the immigrant magicians and later generations.

Lore Kings

As it may be of immediate usefulness, we sketch the history of the magician civilization. It is important to note that, when referring here to ages and civilizations and empires, we speak of the local dungeon and its environs. Other ages, civilizations, and empires take place in the greater world, in parallel and at greater scale.

During the dark age that followed the fall of the Giant Empire, mages were drawn to the donjon, a towering remnant of the Greater Ones from before the Rending. As they grew in power, the mages formed a civilization that brought the dark age to an end.

The magician civilization was ruled by a succession of monarchs, who sought arcane lore lost in the Rending. The Lore Kings discovered much but lost it again in their own apocalypse, which sages now call the Time of Vengeance.

Sometime later, Fearthoht Doommaker rose to dominate the dungeon in an age of villainy that ended with her imprisonment. Now, the dungeon has fallen into another age of monsters, in which the Doommaker Cult attempts to free Fearthoht and promote her to godhood.

Meanwhile, other monster groups vie for power—either through amassing wealth or increasing their numbers—in order to become the dungeon’s next master villain. To determine which monsters form what factions would be overthinking it. Details spill from play.

1 Dowler credits Philip LaRose for the Magician Civilization.