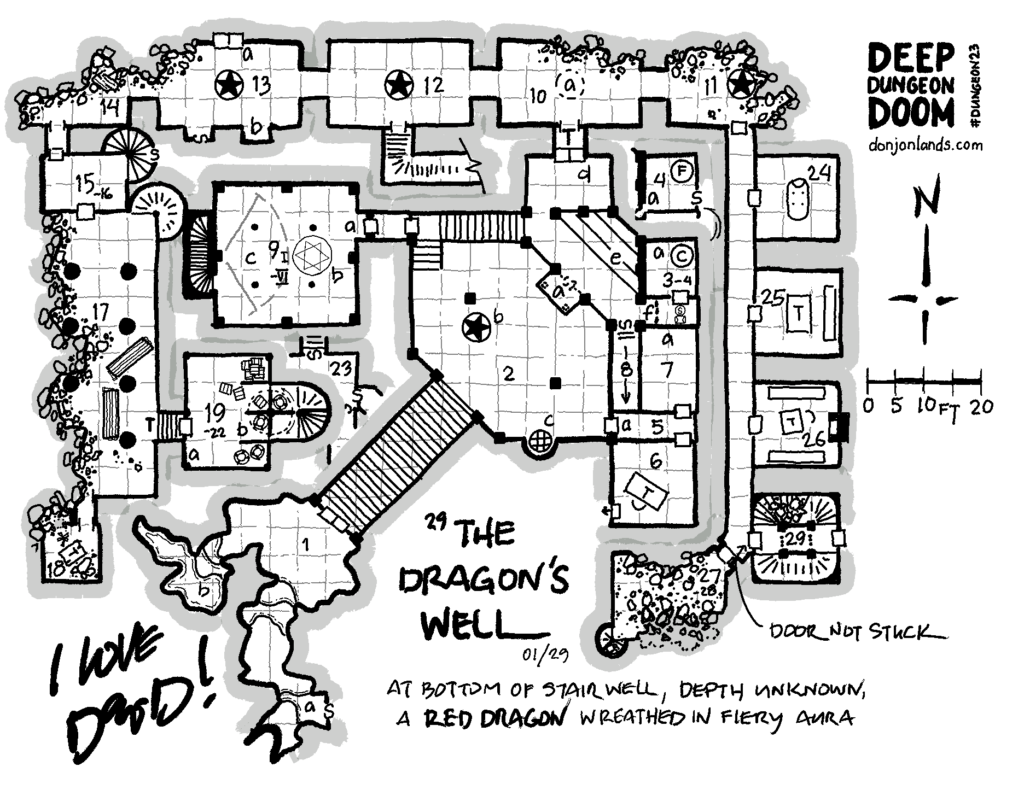

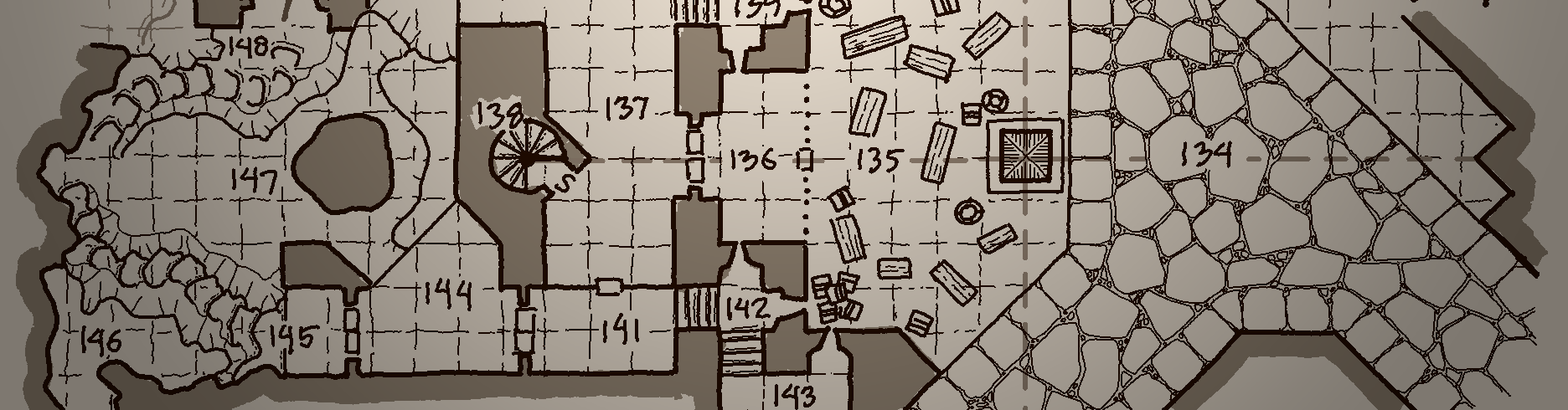

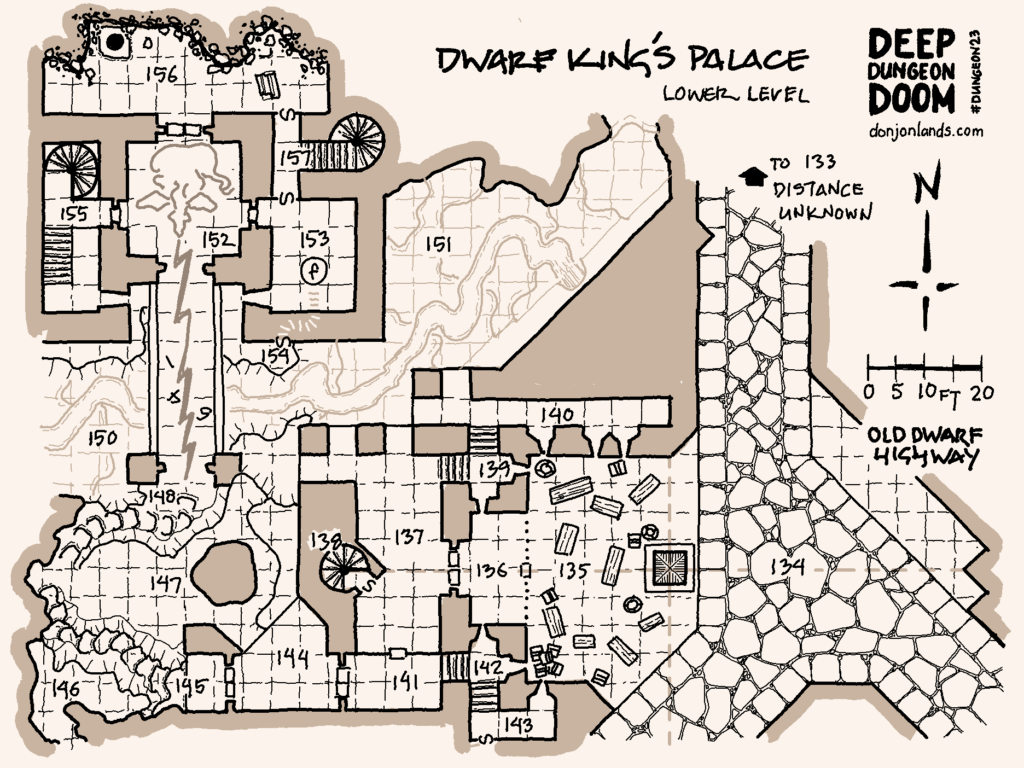

Dwarf King’s Palace—Lower Level

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes a day for a year’s worth of days. Working at my own rhythm, I am more than a year behind. To get details on each room as it is created, follow me on Mastodon.

From Cyclops Curve, we proceed southward along the ancient highway, perhaps more cautious now, as the dwarf may have warned us of the gentle decent into—we presume—the dungeon’s fifth level.

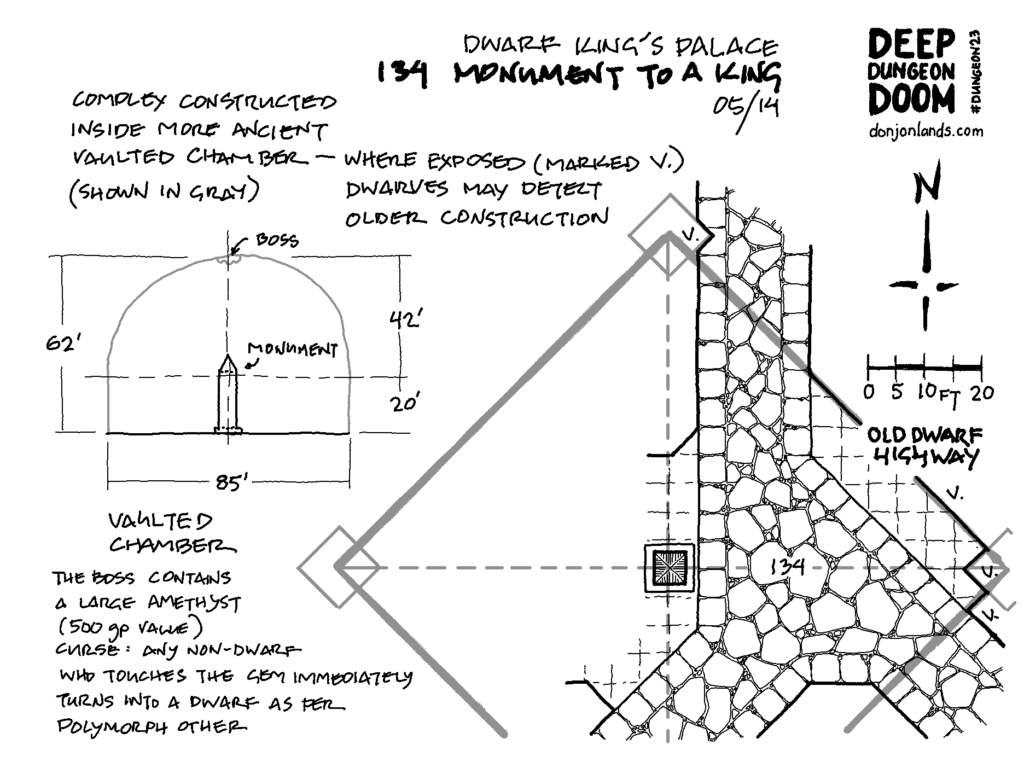

After a long walk, the din of hawking merchants and patron chatter echoes from ahead. Here, a square corner protrudes from the west wall (134, north). Carved on the two sides in dwarvish runes: “Svardin’s Folly.” Overhead, the ceiling opens up beyond torchlight. The dwarf notes more ancient construction.

The din ahead is the Troll Bazaar (135). A rank of hobgoblin spearmen stand guard, either side a granite monument. The monument’s inscription recounts the deeds of Njordr IX, King of Old Stonefast. Atop the monument perches a raven, an eye turned toward us. The merchants are gnolls, lizard men, a troglodyte, and a man with chubby jowls and an enormous girth. The patrons are rogues and treacherous-looking men, as well as orcs, and goblins. The spear men are as cautious of the patrons behind as they are of approaching travelers.

Beyond the bazaar is the Gate of Skulls (136), blocked by a row of iron bars. The walls and ceiling of the barrel vaulted antechamber are decorated in crude carvings of deformed skulls. More hobgoblins, behind the bars with spear and shortbow, guard the central door.

Should we either fight or negotiate our way through the gate, we may proceed west to a loggia (144) overlooking a tremendous geode of purple amethyst (147). We follow rough-cut steps, which descend in a natural cavern (148), to arrive at a bridge across a deep chasm. A dark stream flows beneath.

Crossing the bridge (149), we might catch glinting reflections in the darkness at the edge of torchlight—two eyes wide set, before our hair raises and a lightning bolt crackles along the bridge’s length. It leaves behind sudden darkness and the ozone odor of cooked air.

Welcome to the sixth level of Deep Dungeon Doom.

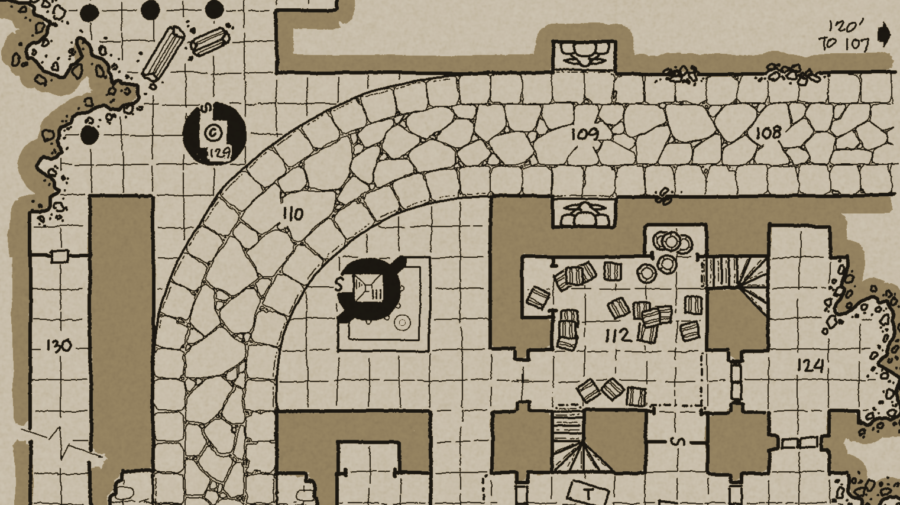

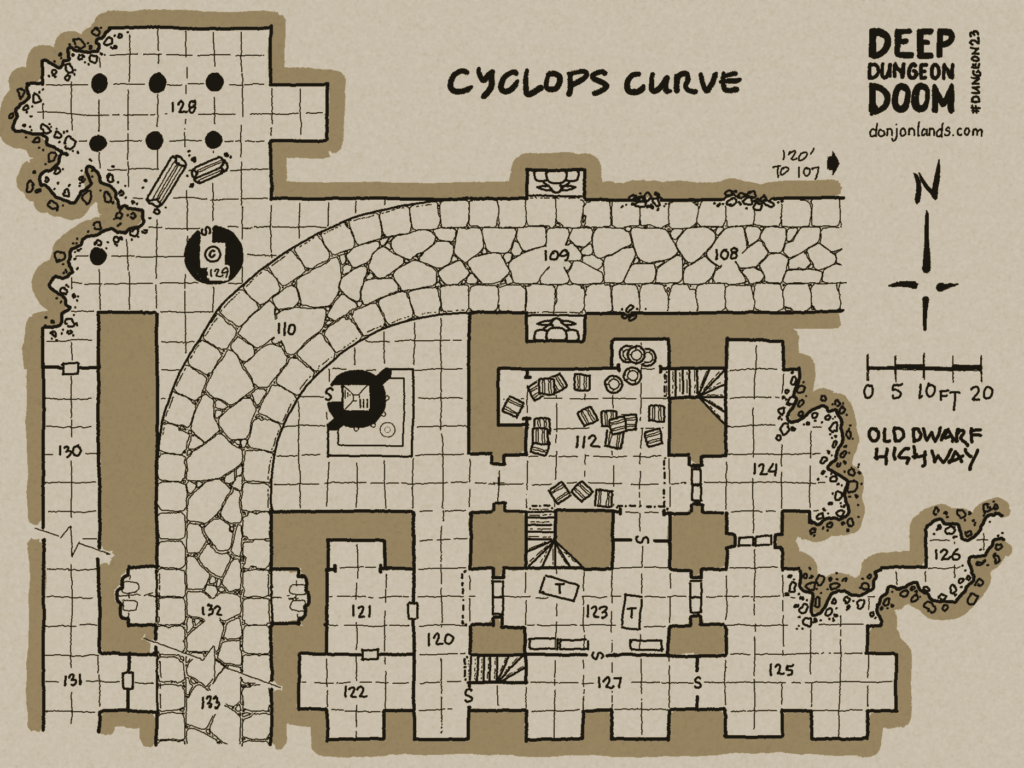

Cyclops Curve

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes a day for a year’s worth of days. Working at my own rhythm, I am more than a year behind. To get details on each room as it is created, follow me on Mastodon.

Should we venture into Fury’s Deep as far down as the exposed archway, we find ourselves on paving stones laid in a mosaic pattern 10 feet wide. Straight rows of square stones border the road on either side under a ceiling 30 feet above. The road stretches into still darkness. This is an ancient subterranean highway. Built ages ago by dwarves who once inhabited these now-quiet corridors, it once traversed their extensive realm.

A couple hundred feet farther on, the highway curves through an open square (110). Two columns flank the thoroughfare to support a high irregular vault.

To the southeast, two levels (upper level not shown) of former dwarven barracks were at sometime converted into laboratories by the Lore Kings. Now, a band of hobgoblin warriors occupies these rooms. The hobgoblins work for a wizard, who may be found deeper in the dungeon. Posted here to guard the entrance, the hobgoblins fell under the charm of a spirit naga, who lairs in the southeast chamber (115). A wyvern lurks amid the columns in the northwest chamber (128).

At the curve, the road turns south. There begins a gentle descent (133), noted only by dwarves, that leads down to the Dwarf King’s Palace on the dungeon’s 5th level.

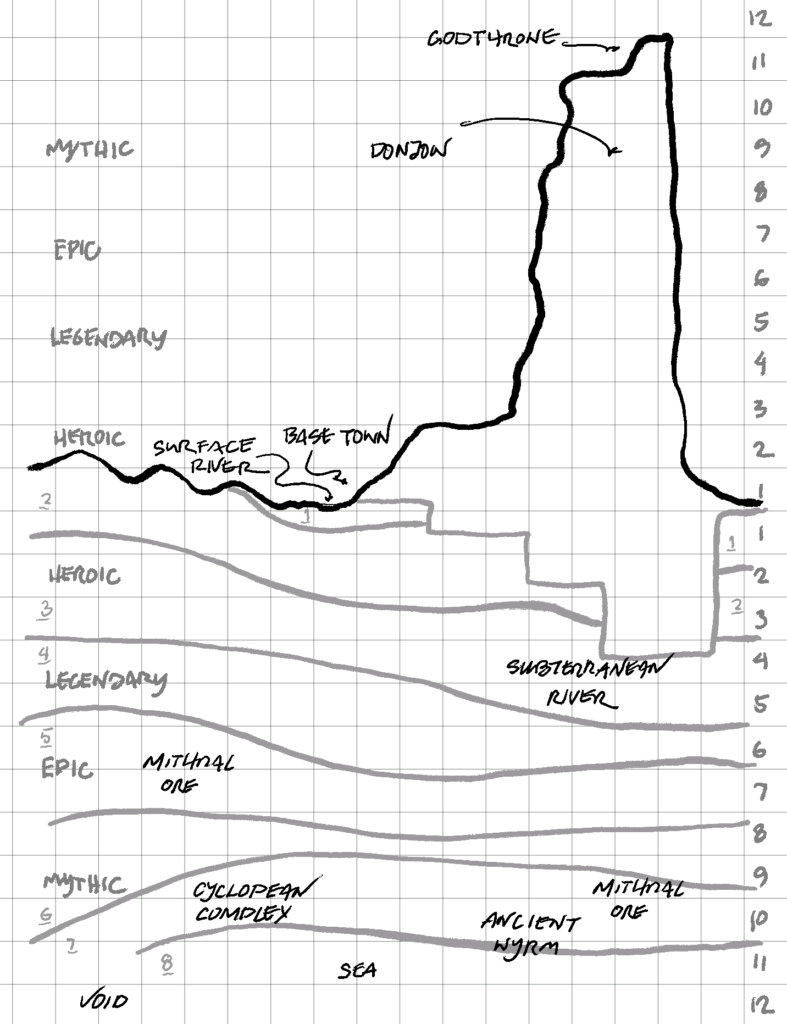

The Dungeon So Far

“Step 3 involves the decision aspect already mentioned and the actual work of sitting down and drawing dungeon levels. This is very difficult and time consuming.” (Gary Gygax, Europa, April 1975, 19)

To what “decision aspect” Gygax refers I know not, but I am intimately familiar with the “actual work” next mentioned. I sat down, for more than a hundred days, to draw dungeon rooms. Difficult? Maybe. Time consuming? Definitely. Enjoyable? I love it!

And then other obligations distracted me, and for more than a hundred days since, I have not been so diligent. Progress on Deep Dungeon Doom halted at the bottom of Fury’s Deep, level 4. I intend to get back to it, but we’ll see if I conquer that dragon. Meanwhile, I continue here with Gygax’s step 3: “The location of the dungeon where most adventures will take place.”

“In beginning a dungeon it is advisable to construct at least three levels at once, noting where stairs, trap doors (and chimneys) and slanting passages come out on lower levels, as well as the mouths of chutes and teleportation terminals” (The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, 4).

Although the mapping pace is one room per day, I take this advice and seek opportunities to slip in ways to get to lower levels. In area 1 Cave Entrance (the first day), I placed a secret door (1a) and a deep pool (1b). Both, I imagined at the time would lead to another level.

Once drawn, a chute marked “to level unknown” hangs in the air until the cartographer advances to the logical terminus. Eventually, the secret door at the Cave Entrance opens into a network of secret tunnels (39) that riddle Lyceum Arcanum. More recently, the deep pool turns out to be the upper end of a watery passage through two areas that begins on level 4 (92 Force Field). An exciting part of #Dungeon23 is realizing that a stairway or chute from an upper level, placed weeks or months before, should come out in the room you are going to map tomorrow.

“Each level should have a central theme and some distinguishing feature, i.e. a level with large open areas swarming with goblins, one where the basic pattern of corridors seems to repeat endlessly, one inhabited by nothing but fire-dwelling or fire-using monsters, etc.”1 (Europa).

Here, Gygax lays out an important aspect of dungeon design long overlooked by my younger self. Early in my dungeon-drawing career, I got the idea that a dungeon was all about what treasures were guarded by what big mean monster in its lair. Certain, monsters and treasures are an integral part of a dungeon. But a compelling theme helps to capture the players’ imaginations, gets them into the dungeon, and holds their interest long after the monster is vanquished, its treasure removed, and the lair restocked. The difference between a collection of rooms and an interesting delve environment is theme.

I summarize Deep Dungeon Doom’s levels as completed, before outlining a few ideas for deeper levels.2 The ideas are mined from the dungeon’s time line (see “Using How to Host a Dungeon for #Dungeon23”). Plans, if executed, may change.

Completed Levels

Lyceum Arcanum [Level 1]

A magic school built during the reign of the Lore Kings and destroyed in the Time of Vengence, it is still haunted by magic-users, living and dead.

Ningalgaur [Levels 2, 3]

Within this area of natural caves, the Illmind first constructed a holding area where they stored brain vessels (any sentient beings) prior to harvest. Only a few wall carvings hint at the purpose. Later, demons converted the structure into charnel pits, carving horrid faces in wall reliefs. To block a deep chasm, dwarves built a fortified drinking hall on the edge of the “Abyss.” The hall is now defended by the Doommaker Cult.

Fury’s Deep [Level 4]

A sinkhole descends over 400 feet to a bottomless pit. Between the surface and infinite depths, a precipitous path winds by access points to several dungeon levels, including a faerie cascade through which is a one-way portal to other worlds and an ancient dwarf-built subterranean road.

Future Levels

Old Dwarf Road [Levels 4, 5, 6]

During their civilization, the dwarves connected their subterranean realm to neighboring dungeons. The sinkhole that makes Fury’s Deep opened access to a still-intact portion of the ancient highway. It runs through a former dwarf dormitory that was re-purposed as laboratories by the Lore Kings and now serves a wyvern as lair. The highway continues down a gentle slope to a bridge across a wide chasm. A river flows below. On the opposite side, a wizard’s tower overlooks the chasm.

Giant Stronghold [Level 7]

The subterranean river flows toward the Abyss (Ningalgaur, above). Along it, a treacherous path leads to an oversize castle built into the rock wall of a high cavern, where the river falls into the Abyss. This was the principle stronghold of the giant empire. A few giants still occupy the place, along with dragons, trolls, and wraiths among others. A clan of ogre magi pretends to sovereignty.

“Garden of Eden” [Level 8]

To increase the quality of the harvest, the Illmind created favorable living conditions for the brain carriers captured on the surface. A nearby magma chamber provides heat. A central orb radiates magical light and darkness in a daily cycle. Fresh water flows through canals. The area became—and yet remains—a lush subterranean forest. Heaven in earth? More like hell, because its inhabitants were aware of their fate.

Sealed Empire [Level 9]

Thanks to a platinum vein, adamantine deposits, and their metalsmithing craftsmanship, the dwarves built an empire wealthy beyond imagination. But they got too curious about the workings of the mysterious device in a deeper level. When the gate opened, a demon horde poured through it. Many dwarves were slaughtered in a great carnage. Survivors fled to the imperial throne room and sealed themselves inside. Though they could not enter, the demons did not retreat for many long years. The location of the sealed door is now lost. Should someone find it and break the seal, an empire’s riches await.

Arena Arcane [Level 10]

The Cyclopes, primordial creatures enslaved by the Illmind, quarried granite from this region. From the space, deep elves later carved an arena. During the giant empire, it served as a slum, before the Lore Kings restored the arena.

Deep Elf City Ruins [Level 11]

The pits and sanctums of an ancient deep elf city are in ruins. The once-magnificent opera house is more or less intact. While they have not lived here in millennia, deep elves frequent the place, seeking lost treasures and forgotten lore.

Infernal Sanctum and Demon Gate [Level 12]

The Illmind constructed the gate to the demons’ home plane. Before departing, they opened the gate to call forth the horde that would destroy any of their remaining works. The dearth of remains from the Illmind civilization testifies to the project’s success. The adjacent sanctum is a cyclopean complex wherein the demons held their infernal revelries.

Deeper

“Before the rules for D&D were published ‘Old Greyhawk Castle’ was 13 levels deep” (Europa).

Ours is to be twelve levels by years end. From the start, I imagined Deep Dungeon Doom to comprise 24 levels at least: 12 beneath the surface, 12 more rising up through the tall tower, called a “donjon,” of the Greater Ones. There are, however, ideas and space for many more levels.

Godthrone [Level 13]

The Illmind built a thing atop the donjon. No one is certain of its purpose. It resembles nothing more than an enormous chair. Hence, it’s common name: Godthrone. The location has been used on and off throughout the millennia as a place of worship.

1 Gygax’s dungeon-level theme examples may seem uninspired to modern adventurers and dungeon makers. In his defense to posterity, the co-creator points out: “The first level was a simple maze of rooms and corridors, for none of the participants had ever played such a game before.” I for one would trade my jade spectacles for a seat at that table.

2 Here, at the crossroads of #Dungeon23 and #Gygax75, I am neglecting McCoy’s precept “Don’t make a grand plan” (“#Dungeon23,” Win Conditions). Rather, the instigator advises: “Just sit down each day and focus on writing a good dungeon room.” Time to get back in the dungeon…

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes per day for one year. I intend to post irregular updates here. To get the daily rooms, follow me on Mastodon.

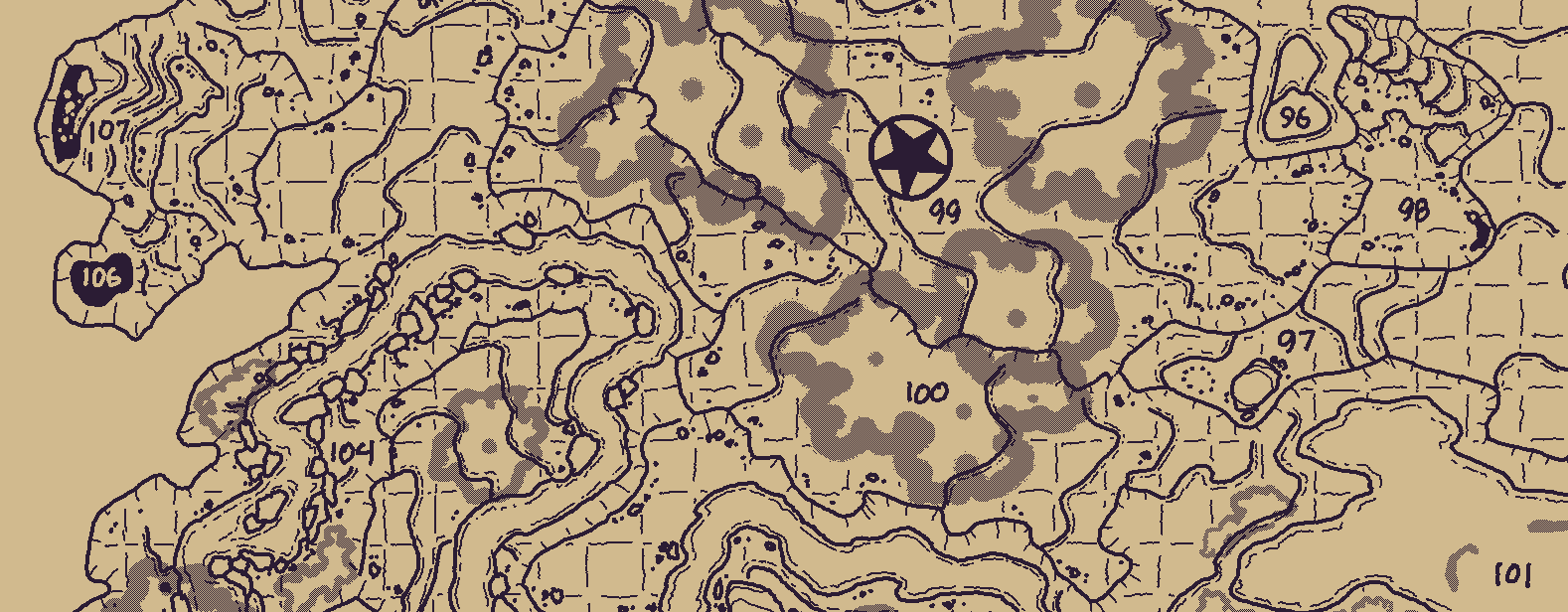

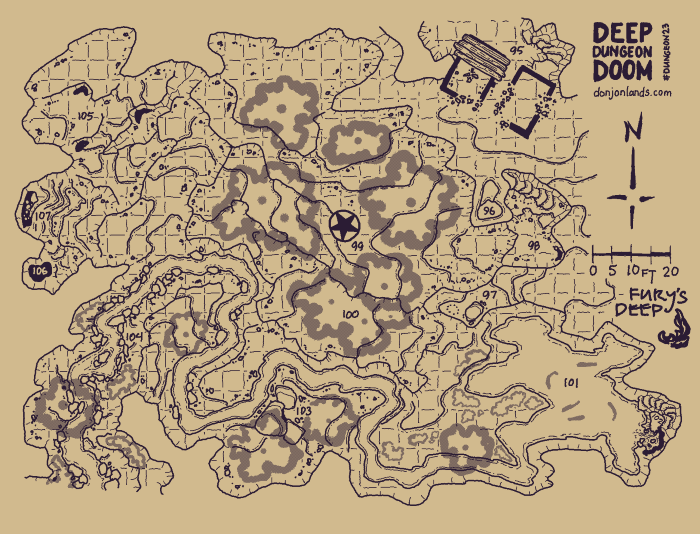

Fury’s Deep

In the middle of a dark night, the ground shook, the earth groaned. Startled from shadowy dreams, the folk of Domesday lay still, wondering throughout the night what new doom had befallen their accursed town.

The sinkhole was soon discovered by goatherds in search of strays in the steep, rocky hills outside town. All was quiet, at first, in its dark depths. Before a year was out, though, shadows could be seen deep down, and after unquiet nights, strange tracks appeared in the narrow gorge that led to the rim.

The townsfolk built a watchhouse to block the only easy access to and from the pit. The post was manned in the day, but none would stay the night after the first such attempt. Avery Dain was a man of 27 years when he came to be called “Oldave,” for he aged a lifetime in that one night.1

Even the daylight shift proved too hazardous. One stormy afternoon the next year, a fury of flames blew from the depths and ravaged the watchhouse and the hills around.

That was a hundred years ago. Now called Fury’s Deep, no one goes there these days save the foolhardy… Save the foolhardy.

Description

A tear in the landscape, Fury’s Deep stretches 110 feet from Rock Point (map 96, northeast) across to Deep’s Dark Defile (104, southwest) and 180 feet from Faerie Falls (102, southeast) to the Carver’s Sand Cliffs (105, northwest). A pit (106) in the western crevasse, over 400 feet down, is said to be bottomless.

An upper floor once joined the two rooms of the Old Watchhouse (95) that straddle the only safe path into the Deep, which is otherwise surrounded by steep granite hills. Steps carved into a rocky cliff once led up to a door, but the wooden upper structure is burned away.

Slipping by the ogres, who lair under a log shelter within the watchhouse, we proceed to a rocky outcrop, called by the locals Witches’ Finger (97), from which we survey our path.

Natural stairs take us to the first precipice (98), down which we must climb or rappel. A hundred feet below, a steep, winding path of rocky dirt leads through Unicorn Grove (99), under the Dryad’s Tree (100), to an Enchanted Lake (101). We then follow the river west, passing Hive Rock (103) and Deep’s Dark Defile (104), before descending farther into the Deep in the northwest at the Carver’s Sand Cliffs (105). A second precipice drops 60 feet onto a slope that slips under an archway of pitted granite stone blocks (107). The archway is about 400 feet below the rim. We avoid the Bottomless Pit (106) to the south.

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes per day for one year. I post irregular updates here. To get the daily rooms, follow me on Mastodon.

Nexus

Fury’s Deep is a nexus, connecting to diverse dungeon levels and other worlds. Except the Old Dwarf Road (107), further development of the following areas are left to the DM.

- 98 Cave of the Unknown: They say no one has ever come out of this cave alive, and it’s true. But no one has ever gone into it, either.

- 101 Enchanted Lake: Nixies live in a complex of submerged caves 80 feet below the surface. The caves may lead to another dungeon level or to an underwater realm beneath the surface of some distant sea.

- 102 Faerie Falls: The 200-foot waterfall hides two passages:

- First, from where it emerges from the cliff, 50 feet below the rim, we can follow the river upstream to the Subterranean Lake (33) in Kubra Kowthar’s Realm (Lyceum Arcanum). Who knows what lies between here and there.

- Second, through a grotto beyond the cascade, we enter the realm of Faerie or that of Grimshade, depending on some unknown factor. Both realms are dangerous for mortal beings. From neither does one easily return.

- 104 Deep’s Dark Defile: Here the river drops into unnatural darkness. I don’t yet know how far down it goes or through what dangerous paths. Eventually, it enters a lower level (probably 8 or deeper) of the dungeon.

- 105 Carver’s Sand Cliffs: These three sandstone cliff faces seem to be carved by a giant hand. Behind this bizarre facade, a nest—or multiple nests—of giant ants riddles the earth. Foraging tunnels may lead to other dungeon levels.

- 106 Bottomless Pit: Descending to a magical void on a lower level, the hole is truly without end. Perhaps the void takes hapless characters to the world’s underside.

- 107 Old Dwarf Road: Beneath the archway, we enter a wide thoroughfare built during the dwarven civilization. We now follow this road farther down into Deep Dungeon Doom.

1 I have the idea that Oldave, despite his apparent advanced years, went on to enjoy a long and successful adventuring career. On retirement, he bought a tavern in Domesday. He became its keeper and occupies the post to this day—for he yet lives, going on his 14th decade and in perfect health!

The Charnel Pits and Caverns of Ningalgaur, Great Lady of Demons, Called the Laughing Fiend

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes per day for one year. I post irregular updates here. To get the daily rooms, follow me on Mastodon.

Progress: For the second time in the year-long daily dungeon-making exercise that is #Dungeon23, I got behind a few days and caught up again in March. Each day’s room often takes me some time more than a few minutes, but I love the work and am so far pleased with the resulting dungeon.

Campaign: Meanwhile, after closing the door on the baalgaur’s prison (Lyceum Arcanum, 9) on the uppermost level, the player party explored the Auditorium’s balcony (2a): The cautious adventurers turned away from three great blades swinging like pendulums in an archway (2d). They then defeated a giant black widow spider (2e), foiled a pit trap in front of a treasure chest (2f), and purloined the gold coins the chest contained. Emboldened by this success, the duo acquired hirelings in Domesday and prepared their second foray into Deep Dungeon Doom.

Ningalgaur [nin-gal-GAW-r]

Named after the nefarious empress and “great lady of demons,” this dungeon region was first used by the demons during their civilization that followed the Illmind’s departure. Most walls, whether natural rock or built from rust-red brick, bare vestiges of relief carvings depicting gruesome faces: bulging eyes, bulbous noses, fat cheeks, wide mouths grinning, lascivious lips, rolling tongues. Since then, a succession of civilizations and empires have connected the former charnel pits with tunnels to create a dense network of rooms and caves.

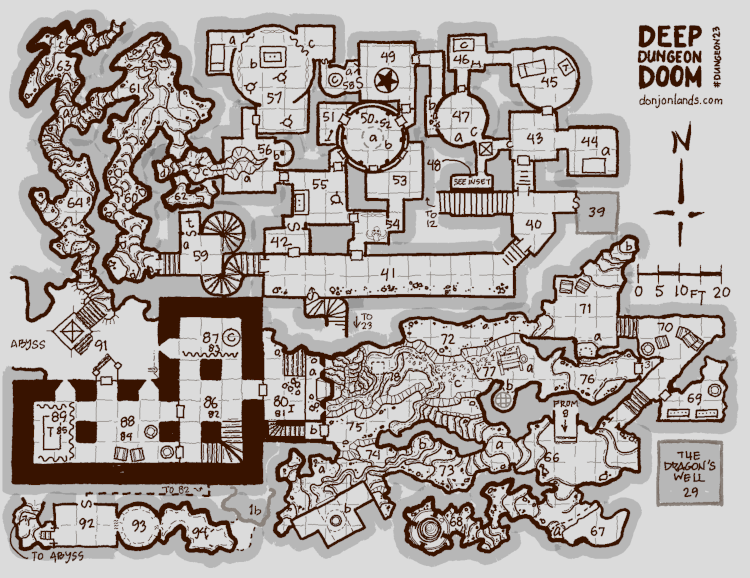

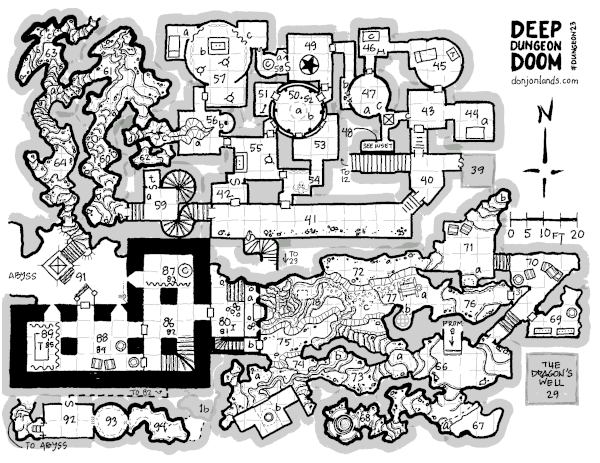

Now, with its 55 encounter areas (40-94) spread across levels 2 and 3, Ningalgaur may be divided into four sections: Minotaur Maze (NE), Veiled Grotto (NW), Laughing Rift (SE), and Daemningstadr (SW). A brief description of each follows the map.

My thanks again to Tony Dowler for his How to Host a Dungeon: The Solo Game of Dungeon Creation (2nd Edition, Planet Thirteen, 2019), whence I draw the civilizations: demonic, dwarven, and magic-using. You didn’t think I came up with a fortified drinking hall myself, did you?

Minotaur Maze (NE)

A deluded magic-user employs illusion, polymorph self, and a hero henchman in a bull’s-head mask to discourage trespassers. It’s Scooby-Doo meets Theseus and the Minotaur, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a real minotaur in there.

Veiled Grotto (NW)

A lost pebble sheds an impenetrable darkness throughout these natural caverns filled with noxious molds and creeping animals. Largely considered impassable by the locals.

Laughing Rift (SE)

A deep chasm connects diverse regions of the dungeon, this level and beyond. A mad hermit holes up in natural caverns below a dwarf-built dam on the south rim. Nearby, a magic portal wants repair. Carved tunnels on the north rim are presently inhabited by gnolls, who dispose of their waste in the rift’s nether regions and guard the entrance to Daemningstadr.

Daemningstadr (SW)

Built during the dwarven civilization, Heillwaegg Daemningstadr Drekkenhal—in the common tongue, “Drinking Hall of the Blessed Wall in Dam’s Site”—is a fortified construction, now occupied by members of the Doommaker Cult. The priest-leader’s mission is to destroy remnants of the Gold Flame, which defends the Bastion of Law on Level 1, to make way for the cult’s main objective in the dungeon’s shallow levels: to release the balgaur from its prison in the Infernal Tower.

Doom’s Door: Death Trap Design

“Zap! You’re dead!” J. Eric Holmes warns against these sorts of traps in the 1977 Basic D&D (40). I tend to comply. Sometimes, though… sometimes!

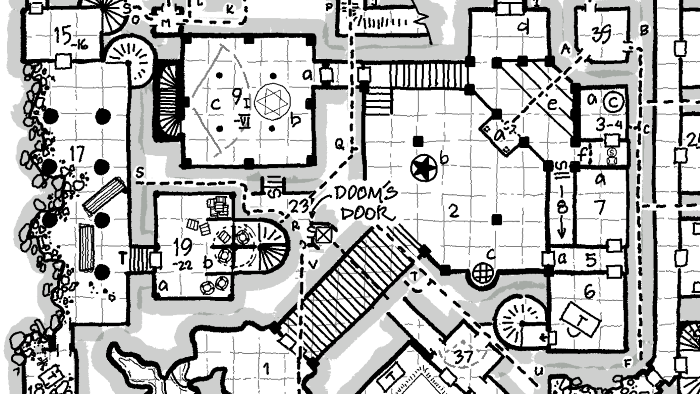

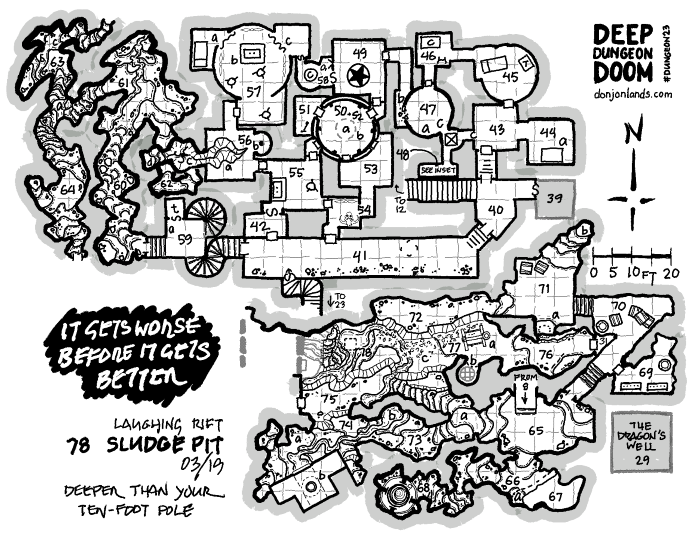

During the daily cartography exercise that is #Dungeon23, I noticed an auspicious alignment. Let us go to Deep Dungeon Doom’s Level 2 (image above). From room 37 in Kubra Kowthar’s domain, a corridor runs northwest to an apparent dead end. Stopping to search for secret doors—as adventurers do—we stand above Level 3’s Laughing Rift.

I am doomed to put a pitfall there. The floor opens beneath our feet. We fall 110 feet to the rocky floor below—Zap!

Holmes lets us get away with such a trap, though, if “a character might avoid or overcome [it] with some quick thinking and a little luck.” With that in mind, we set about to give ourselves a chance.

Warning

Beyond the secret door—for one there is—room 23 lies at the bottom of the Bastion of Law. Carved into the stone block wall that disguises the secret door is the following warning:

YOUR DOOM LIES BEYOND

FOR BEYOND YOU LIE BELOW

On our side of the door, we read a similar inscription:

YOUR DOOM IS UPON YOU

FOR YOU ARE UPON YOUR DOOM

Ignoring the warning—we’re adventurers after all—we find the secret door, whose presence we think obvious. The trap is armed when the opening mechanism is engaged. From room 23, we would walk through, into the space beyond. From this side, the floor opens beneath us.

Chance to Spring the Trap

If the DM is a little soft, we might say the trap is not maintained. It engages when weight is upon it only one-third of the time, to use a B/X-ism (B22).

Saving Throw Conditions

Further, the aperture is 3 feet square. The tight fit allows us a save vs Turn to Stone to catch ourselves with outstretched arms, feet kicking in the void, fingertips gripping a floor stone’s edge. Quick comrades have a chance to snatch us from fate. Otherwise, we might be able to haul ourselves out on our own. DM’s call. This DM would ask how we intend to do it.

Failing that, we have time to feel heart rise to throat, as we plummet into darkness.

Unexpected Deliverance

One last chance. Directly below, the Sludge Pit (78) awaits. We save vs Dragon Breath to take half 11d6 damage.

We still have to wrestle off any armor before drowning and swim to the surface through viscous muck. Then we find ourselves all alone and sans armure at the nethermost point of the Laughing Rift—Zap! Welcome to Deep Dungeon Doom!

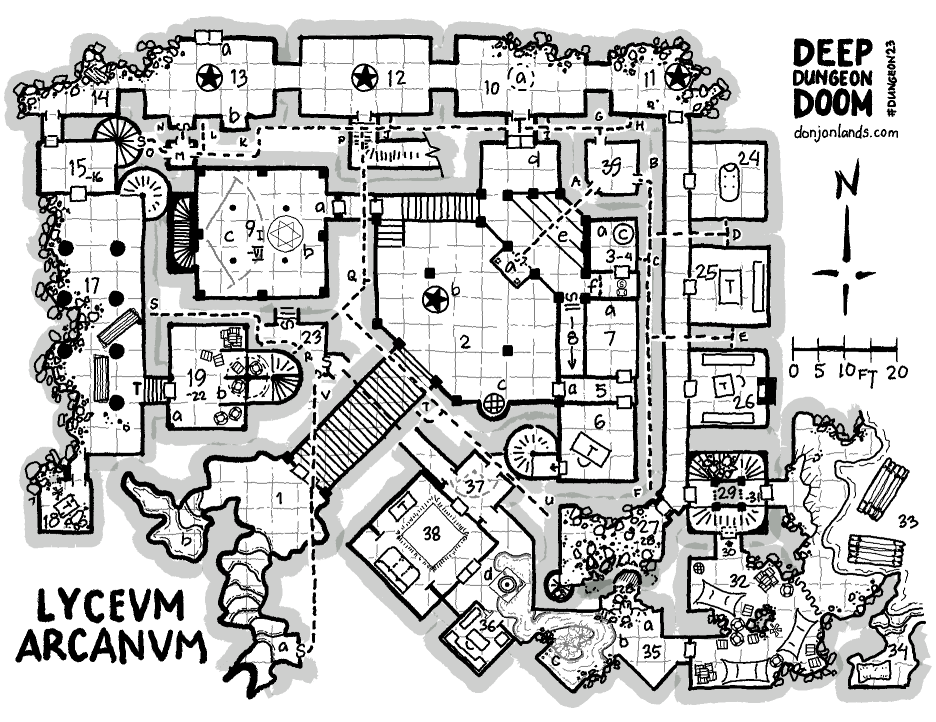

LYCEUM ARCANUM

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes per day for one year. I post irregular updates here. To get the daily rooms, follow me on Mastodon and Twitter.

Extending from the first level and into a second-level sublevel of the dungeon, LYCEUM ARCANUM comprises 39 areas and includes four buried towers, three surface entrances, 11 exits to the first, second, fifth, and unknown levels. It contains myriad secrets and untold riches and magic items, guarded by diverse traps, a cast of magic-users, a lesser djinni, and a baalgaur.

The player party, a pair of neophyte adventurers, descended to the Auditorium (2), took the bronze mask from the statue (b), which they then toppled, and opened the brass door to Baal-Dagan’s Prison (9).

Domesday and Environs

In Deep Dungeon Doom, I follow #Gygax75 and #Dungeon23 to create a D&D dungeon campaign in a few minutes per day for one year. I post irregular updates here. To get the daily rooms, follow me on Mastodon and Twitter.

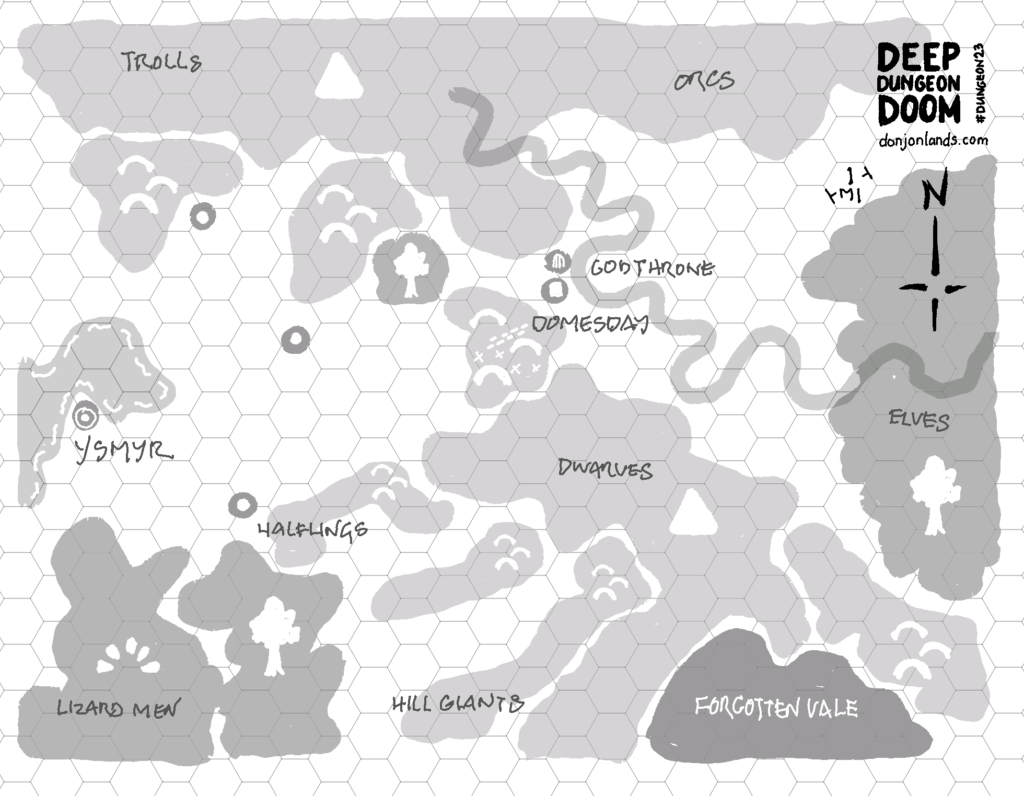

“Step 2 requires sitting down with a large piece of hex ruled paper and drawing a large scale map. A map with a scale of 1 hex = 1 mile … will allow you to use your imagination to devise some interesting terrain and places, and it will be about right for player operations such as exploring, camping, adventuring, and eventually building their strongholds” (Gary Gygax, Europa, April 1975, 18).

Making the Wilderness Map

Scale

We might assume a “large piece of hex ruled paper” is tabloid (A3) size, although I have no idea where one would acquire hex paper in the mid ’70s, especially tabloid size.1 Even at that size, one mile per hex makes what seems to my eyes a too-small area for building strongholds. I suppose I’m used to establishing a barony and having extensive space to explore.

When perusing Dave Arneson’s First Fantasy Campaign (Judges Guild) map and text, though, I imagine a more intimate setting for several PCs and their interactions, the 1977 map’s scale notwithstanding.

Furthermore, with Deep Dungeon Doom’s focus on the dungeon, a small wilderness area feels right, and Ray Otus points out that we’ll have “time to draw a larger scale map in week 5” (The Gygax 75 Challenge, 11).

The reMarkable gives me a hex grid that comes out to ½" hexes on a letter-size page.2 One hex per mile—and limiting the map size to 8" × 10", so as to fit on either US letter-size or European A4 paper—gives us an area of 16 × 20 miles or 320 square miles. Intimate.

Settlements

Following Otus, I place a large town on the coast and a couple villages support-distance away. I like to work in as many terrain types as is logical for a map’s aesthetic appeal and to exercise the wilderness encounter tables, which are differentiated by terrain.

Mysterious Locations

I choose a remote, vacant area between highlands for a mysterious location. I don’t know why the vale is forgotten or why it might be important to the campaign, but I’m guessing it’s got something to do with the Doommaker herself.

Also, inspired by the real-world map source, the central hills connecting the north and south mountain ranges also mark a geographical divide between the eastern highlands and the western lowlands. A long, straight, sloping tunnel runs between the two. Parallel to it, a series of level tunnels joined by sheer precipices runs the same length. Both structures are huge and blocked by rubble, debris, and monsters. A surface-level track also traverses the hills.

Cyclopean Tunnels

The parallel tunnels are a remnant of the Greater Ones. The sloping tunnel was used for ground transport. The other, after the builders diverted the river, was a series of locks for watercraft. The elves of the eastern woods re-diverted the river some longtime ago.

Dungeon and Base Town

The dungeon, which I name after its most prominent feature, is located off-center, and I place the base town—a stronghold—nearby. I also add regions inhabited by PC races, plus monstrous races for tension.

So early in the campaign—the PC party is still practically at the dungeon entrance, I don’t expect the neophyte adventurers to explore the wilderness soon. I highlight only geographical features on the map, marking each with a single large icon, and restrain myself from adding further detail—apart from an encounter table.

Wilderness Encounter Table

I divide the wilderness map into quadrants, marked by the central hills. Entries separated by a pipe “|” should be read west|east; those by a slash “/” north/south. For example, a 3 result yields halflings when traveling in the west or elves while exploring east of the central hills.

| 2d6 | Result |

|---|---|

| 2 | Magic-User (Men*) (L or N) |

| 3 | Halflings|Elves |

| 4 | Knights** |

| 5 | Orcs/Dwarves |

| 6 | Men*|Humanoid* |

| 7 | Roll on Wilderness Encounter Table* |

| 8 | Bandits |

| 9 | Lizard Men|Goblins |

| 10 | Ogres |

| 11 | Trolls/Hill Giants |

| 12 | Magic-User (Men*) (C) |

| * See Wilderness Encounter Table (X57-8). ** Knights? I don’t know yet. |

Daily #Dungeon23 Rooms on Mastodon and Twitter

I post the dungeon map, updated with the day’s room and a brief description, every day on Mastodon and Twitter.

1 Avalon Hill of course. In “Hexmaps and Random Encounters Before D&D,” Tom Van Winkle notes that the makers of Outdoor Survival (1972) sold 22" x 28" hex maps for amateur game designers (Tom Van Winkle’s Return to Gaming, September 2, 2023). In an email exchange, Tom points me to a notice in the July 1964 issue (Vol. 1, No. 2) of the Avalon Hill General. Under the heading “Design Your Own Games” on page 1, AH offers the large hex maps in sheets for $1.00 each.

2 Only interesting for reMarkable users: To achieve half-inch hexes, I use the reMarkable template medium hex grid, portrait orientation, exported to PNG, and printed at 176 ppi. Use the highlighter in different colors and export grayscale to get the varying shades. I have to turn the tablet landscape, because reMarkable got the hex orientation wrong. The engineers maybe never played Outdoor Survival, whose map board has the horizontal lines at top and bottom. This is, therefore, the “correct” orientation.

Added footnote 1. [19:04 8 September 2023 GMT]

Edited footnote 1 to include the source. [5:45 11 September 2023 GMT]

First Twelve Days of Deep Dungeon Doom in Video

A megadungeon in one room a day for 365 days in 2023. These are the first 12 days of Deep Dungeon Doom, a #Dungeon23 project.