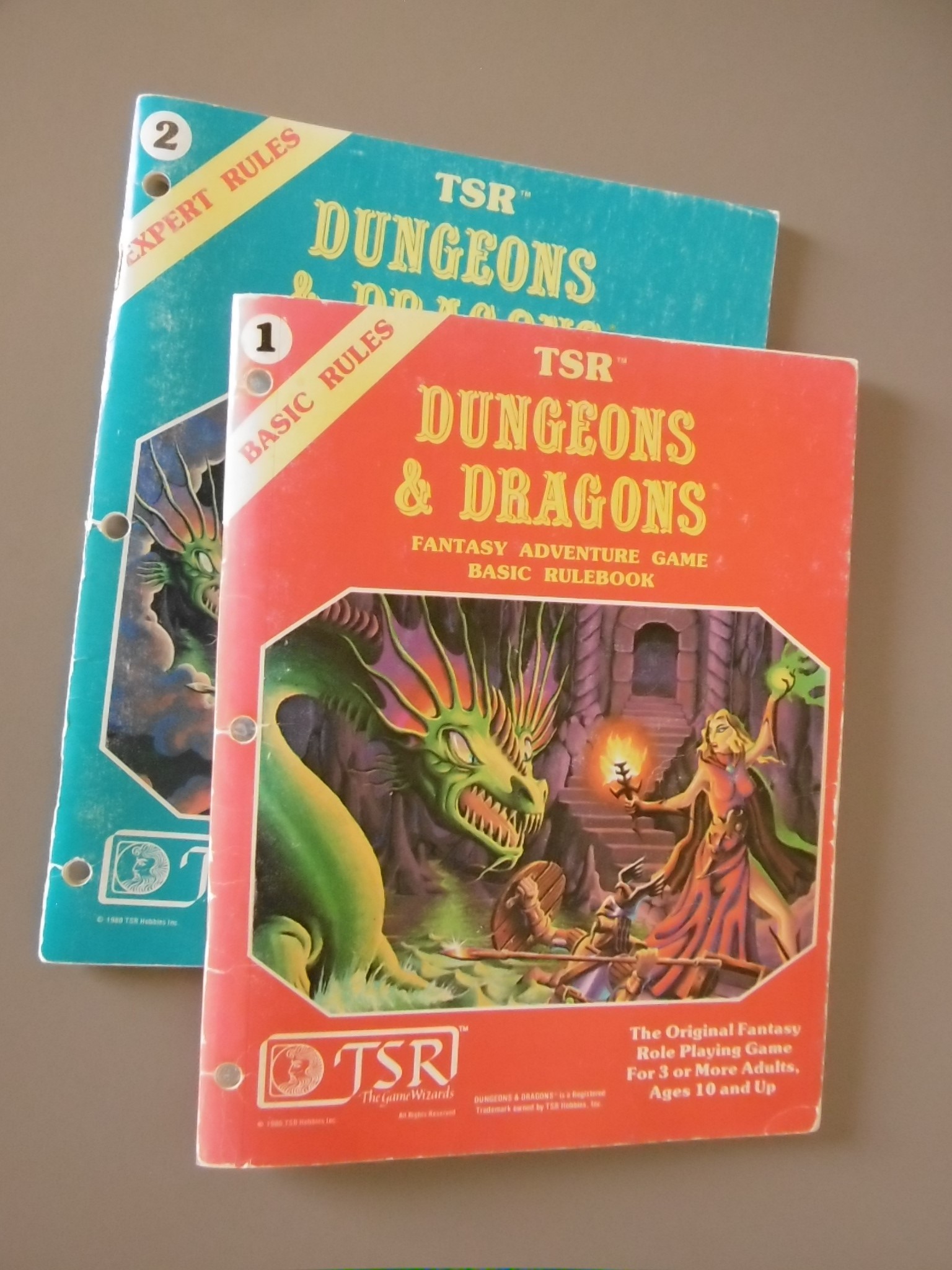

We’re almost ready to play. We’ve covered everything that happens in the depths. Left for us now is to consider what happens when our adventurers are outside the dungeon.

I want only to cover aspects critical to the scenario. I intend to run The Deep Halls as a solo game, which also serves as an impromptu pick-up game for friends. In such games, the action is focused within the dungeon’s twisted corridors; “Base Town” is for rest and resupply, sometimes—as dictated by the scenario—with a loose connection between the two, which allows for further development in play.

“It isn’t so much the wealth as what the characters might spend it on that poses a problem. Assuming they invest it to ensure the success of further explorations, the obvious acquisitions are hirelings and spell scrolls.”—from “More XP for Treasures”

One critical aspect, in the case where treasures are generous in the closed dungeon, is that we may desire to minimize the impact of over-wealthy player characters. The following points are intended to accomplish that by extracting some gold and putting pressure on the characters to return to the dungeon.

Even with normal treasure amounts, such as when using the default Flying treasure sequence: 2-1-½, the following points are worth considering, if only to preempt the occasions when the party recovers large and valuable treasures. Such windfalls are not rare in the game, and you don’t want to surprise players with a sudden necessity to convert found coins to the king’s currency at a high rate.

We want to allow magic-users to make scrolls—it’s a special capability of the class and augments the magic-user’s often limited arsenal. But we don’t want them to be too comfortable while they do it.

Likewise, a few non-player characters round out the party’s range of abilities and give the party more tactical options. Not to mention the entourage is part of the old-school experience.

Though the treasures are well hidden and often trapped, adventurers should still find them, and though the gold is reduced by fees and conversion rates, the characters should ofttimes retain great wealth. All the while, there must remain a sense of wonder in its finding and a sense of satisfaction in its judicious spending.

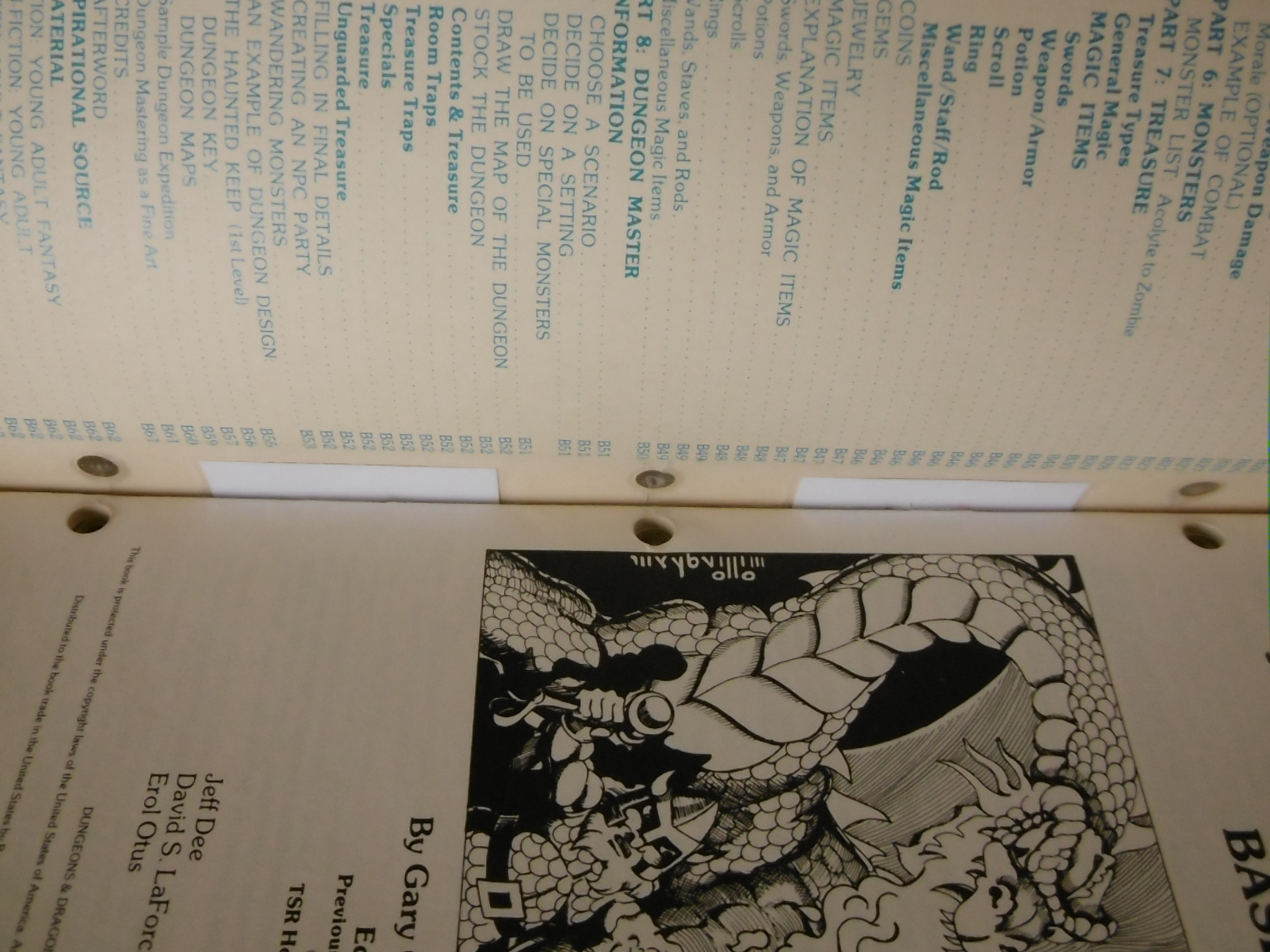

Reading Map

Treasures, Hidden, Trapped

“…augmenting the whole by noting where and how the treasures are protected and/or hidden.”—Monster & Treasure Assortments on the disposition of treasures

Reading “protected” as trapped or guarded by a monster, a complacent DM might be satisfied to hide or trap treasures not in close proximity to an alert monster and leave treasures with monsters otherwise unprotected. This may be a mistake in any adventure and, in a game with extra treasures to be found, is sure to lead to “no challenge, no thrill…”

I have mentioned before that M&T provides tables (reproduced in the AD&D DMG) to assist the DM in this regard. I suggest that most—if not all—treasures should be hidden or trapped and many hidden and trapped, especially those without monsters. Leaning heavy on the tables to begin, the DM will learn, I should think, to invent other interesting containers, insidious traps, and imaginative hiding places before the tables’ options become too commonplace.

Restocking the Dungeon

Monsters reinvest a cleared room in one to four weeks. You might inform the players of this fact or let the characters learn the frequency over the course of a few return forays.

One to four is 2.5 weeks on average. A party might risk one week, maybe two, for magic-users to make scrolls. By the third week, the party is likely to be anxious to get back. To increase this comfort zone, the DM may lengthen the period by rolling more or different dice, say d6 (mean 3.5) or 2d4 (5 weeks).

We might also say that when the party passes through a previously-cleared and still-empty room the period is reset.

Base Town

A brief interlude to discuss the other critical aspect concerning the scenario as a pick-up game, which is the development of the party’s operations base. We assume the adventurers return to a town or city to recuperate between dungeon expeditions. They find there the usual necessities: inn, tavern, markets, church or temple, magic-users and thieves guilds, and a local authority. For our purpose, other than exploiting any obvious connections between town and dungeon, the “Base Town” needn’t be further described.

Organic Base Town

organic adjective

2 c : having the characteristics of an organism : developing in the manner of a living plant or animal

—Webster’s

A DM may add details before play begins as he or she sees fit or allow the base town to grow as the campaign progresses. That is, add details to the town only as necessary and only in play or as a direct result thereof.

This latter approach, in addition to reducing preparation time, allows the base town to be different only in ways that relate to the campaign and to the player characters. Moreover, ideas may come from elsewhere in the table’s brain array. The players then feel some agency in the base town’s development, and it becomes as much home as base.

Whether mundane or fantastic, if an element departs from the ordinary for a medieval fantasy town, it is somehow important to the story. This is not a rule but the result of the guideline: add details only as necessary in play.

The Church Connection

An obvious connection between Base Town and The Deep Halls we might make from the beginning is the local religious authority. To allow the seed to grow, we keep this connection loose. Let’s say the local clergy knows only that a sect of priests constructed a dungeon in the wilderness. The clerics do not know the dungeon’s exact location, the nature of the sect, or its goals.

Church or Temple

I use “church” for the local religious authority. In my mind, a church is dedicated to a monotheistic deity—or at least the chief among lesser gods—and a temple is dedicated to a pantheon of gods or a single god among a pantheon. The DM, of course, may use church or temple and define them as desired.

Wealth Extraction

“If the Gentle Reader thinks that the taxation he or she currently undergoes is a trifle strenuous for his or her income, pity the typical European populace of the Middle Ages.”—Gary Gygax, Advanced D&D Dungeon Master’s Guide (TSR Games, 1979)

In the DMG’s chapter on “THE CAMPAIGN,” Gygax devotes a section to the careful extraction of excess wealth from the game. Under the summary heading “DUTIES, EXCISES, FEES, TARIFFS, TAXES, TITHES, AND TOLLS” (90), he covers the diverse taxation practices of medieval Europe and gives examples from a town in “the typical fantasy milieu.” We may apply a few methods to our scenario.

The purpose of the Gygax tax is to remove some wealth—once we’ve got the XP out of it. To avoid tedium, we consider only methods that take large sums. We don’t mess with a few coins here and there or even percentages in the single digits. We target rather the tithe level and above, and we institute the methods from the first town visit. The extraction should seem to the characters normal and become routine. Players may learn to envision 90% of the great mound of treasure as they shovel coins into large sacks.

Parenthetical amounts below are suggestions only.

Magic-users Guild: An annual fee (100 g.p.) gives access to spells when gaining a level as well as access to a research library for free (10 g.p. per visit for non-members). At 9th-level and above, the fee is ten times the base rate (1,000 g.p.) and also grants laboratory space.

Thieves Guild: A thief character is expected to pay the annual fee (100 g.p.). Any who are not aware of the custom are reminded by a group of the guild master’s thugs in ungentle fashion. Among the typical benefits, a member may hire adventuring thieves and inquire about potential buyers for particularly interesting and valuable treasures. All “benefits” come at the price of bribes, payoffs, and kickbacks (100 - 1,000 g.p or from 10 to 50% of the transaction).

The Church: The devout, including most clerics, attend services and rituals, purchase holy water, and regular tithers may consult the small collection of religious texts. Regular tithers, moreover, may receive, at higher levels, special consideration when in need of healing or other forms of clerical aid, such as cures and curse removal, up to restoration of life.

Restorative Spells: The progressive degrees of clerical aid are freely available to all faithful followers of the local religion. This, at the discretion of the clerics, who reserve their daily spells for the devout and hard-working local folk who don’t put themselves in harm’s way in dark places. Those who do not tithe, or who are less than devout, may receive such aid at the cost of a donation (1,000 g.p. × spell level or 1,000 g.p. × caster level or as high as 1,000 g.p. × the square of the spell level; raise dead then requires a 5,000 to 25,000 g.p. donation).

Money Changer: Assume any precious metal pieces hauled out of the dungeon are not “coin of the realm” but foreign and ancient monies. These are not accepted in local shops, for there is a steep fine (50%) for possession of foreign currency. To avoid the fine, holders of such coin, upon entry to the town, must declare the illegal tender at the gate and proceed immediately to the money changer’s office. The two are in close proximity. The money changer takes 10% for the local authority.

Buying and Selling Gems and Jewelry: Gems, jewelry, and other such valuables can be bought and sold at the money changer’s or at the markets. A luxury tax (10%) is exacted.

Robbery: The innkeeper advises against storing wealth in a “secret place” at the inn or elsewhere and declares the establishment free of responsibility. Assume that any treasure so hidden—and unguarded—will be robbed in the character’s absence 20% of the time.

Bank: More secure than under the mattress, renting a coffer at the bank is just as sure to be safe as it is to have a cost (10 g.p. per month for a small coffer—holds up to 300 coins; 30 g.p. per month for a large coffer—1,000 coins; and 200 g.p. for a chest—10,000 coins). The banker assures the characters that the vault, as the property of the local authority, is guarded by men-at-arms and magical wards. Any robbery attempt should prove the vault secure and put the criminals in another dungeon or under the executioner’s axe.

Upkeep: Taking as examples the Travelers Inn and the next-door Tavern from The Keep on the Borderlands, we may fix daily upkeep at one gold piece for lodging, another for food, and a third for drink. We might round that off to 20 g.p. per week, then raise it to 30 g.p. per week per character to include incidentals.

The Complaints Department

If players complain about the dwindling trove, you might simply explain the meta-game rationale: the dungeon is full of treasure to allow a clever party to gain enough experience to be viable opponents against deeper-level denizens; excess wealth is extracted.

If characters complain, you might give a name to the local authority, to whom they may direct their ire.

Hireling Health and Happiness

The number of hirelings is limited to some degree by the characters’ Charisma scores. Still, at five non-players for each character, we have a large troop blundering in the dungeon.

Hiring

“The player wishing to hire a non-player character ‘advertises’ by posting notices at inns and taverns, frequents public places seeking the desired hireling, or sends messengers to whatever place the desired character type would be found (elf-land, dwarf-land, etc.). This costs money and takes time…” (Holmes, 8)

Holmes proposes 100 g.p. × the roll of a six-sided dice for the inquiry alone. I have balked at this figure for going on 40 years. In the case where the player characters are in possession of such wealth, though, it seems not unjustified.

We might say, without getting into great detail, that each class type is found in different venues: fighting men at the inn or tavern, clerics at the church, and magic-users and thieves from the guilds. Further, to enable Holmes’s reference to elf- and dwarf-lands, let’s assume those races are not common in the immediate region and that adventuring hobbits are likewise scarce.

Holmes goes on to suggest 100 g.p. as a minimum incentive to join the party. If we borrow the HOSTILE/FRIENDLY REACTION TABLE (Holmes, 11) for the purpose (as in OD&D but not specified in Holmes), offers of 200 g.p. and higher garner a bonus on the roll, and “uncertain” reactions require the hiring character to “make another [higher] offer” before another roll is made.

Reputation

The party with a reputation for good pay and decent treatment finds hirelings when desired. A generous party or individual characters may find that hirelings seek their employ. Conversely, if the party earns a poor reputation, the hireling pool may run dry—the minimum offer doubles and trebles and penalties on the reaction table accrue.

Pay and Bonuses: In addition to the initial incentive, hirelings should be rewarded with an equal share of treasure. Extra coin and magic items are considered bonuses and increase the employer’s reputation.

Party Success and Hireling Survival Rate: An oft-ignored factor in considering a party’s reputation is their overall success in adventures and how often they return with a lifeless hireling over a shoulder or, worse, without the hireling at all. Adjust enticements and reaction rolls accordingly.

How Many Hirelings Too Many?

As long as everyone is having fun, it isn’t too many. Two points to be aware of are overcrowding and combat encounter length.

If the group enjoys a good long melee, they are well served by a large entourage. There is, however, a point of diminishing returns. As party size grows, so does the number of monsters per encounter. Space, determined by map scale, limits the number of party members that can get in the room. The party that cannot bring its full force to bear against the larger number of monsters loses the melee—though the door is well guarded.

For melee-loving groups, consider a larger map scale. Not by coincidence, at 30 feet per square, the scale becomes ten yards, and The Deep Halls a battlefield. The dreaming priests in their reverie now command an army, and your old copy of Chainmail gains new life.

After figuring the volume required for coins (see Note 2, “Recalculating a Coin’s Weight”), I revised the rents and sizes of bank storage. [17:15 6 February 2022 GMT]