Terrain Effects

Strategic Movement

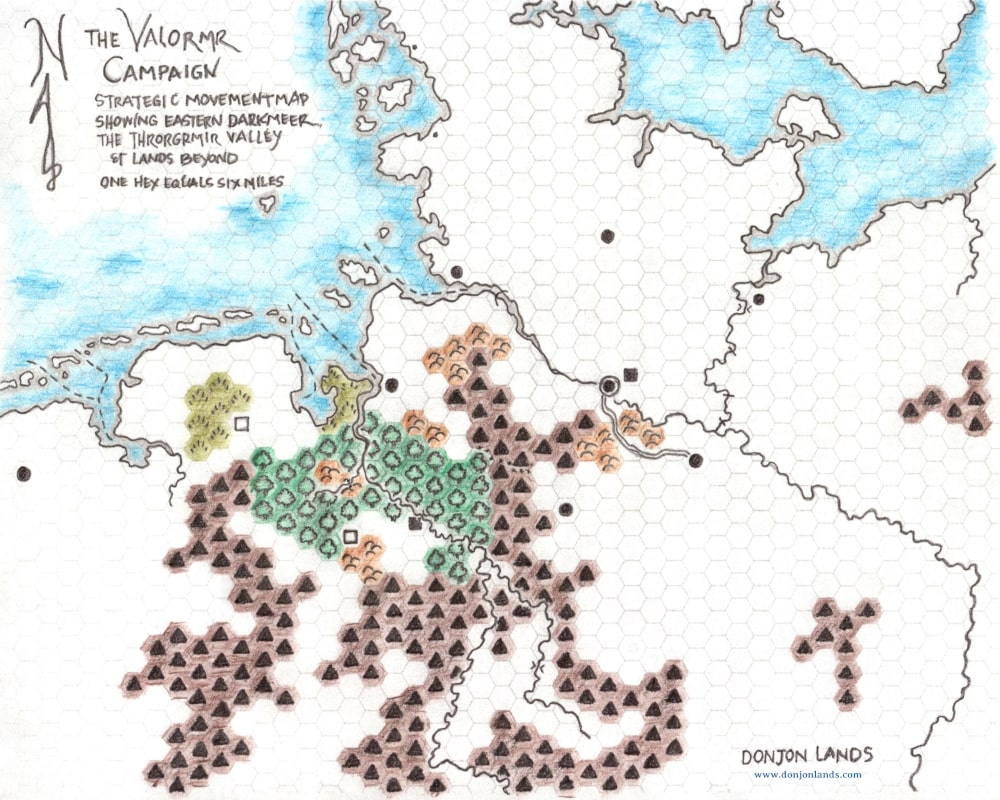

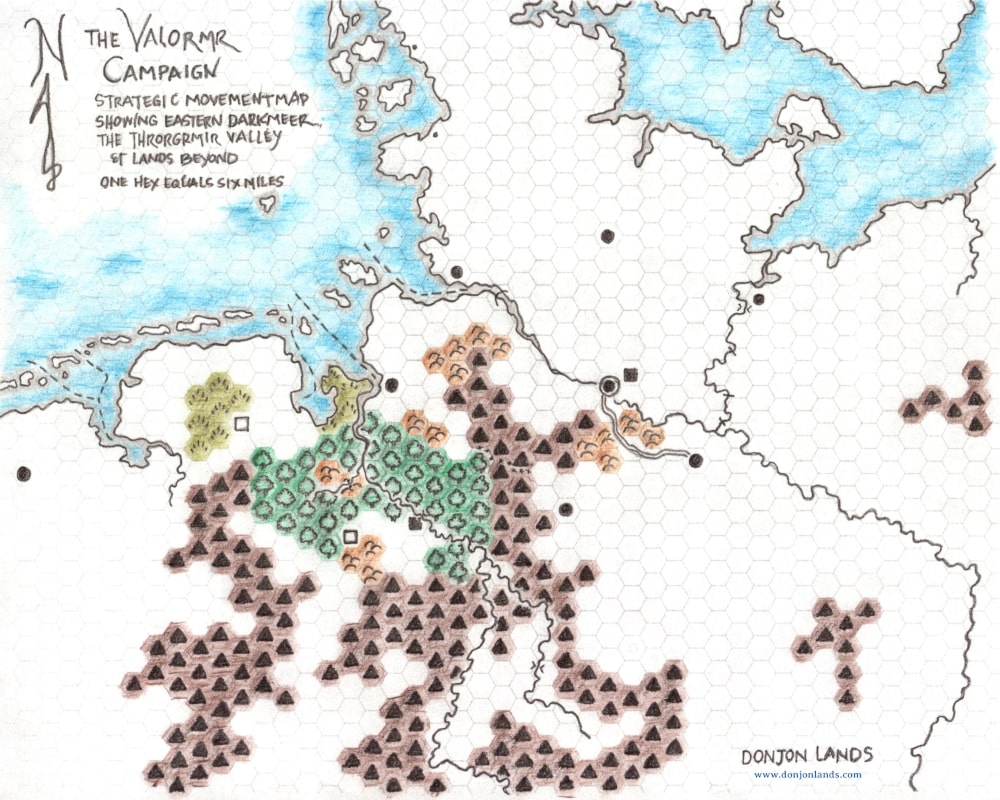

This is the fourth of five articles, which discuss strategic movement in the Valormr Campaign.

- Strategic Movement (Introduction)

- Overland Travel

- Waterborne Transport

- Terrain Effects

- Weather

Movement by Terrain Type

The table below gives the point cost to move into a hex of each terrain type. Some terrain types have other considerations, described below.

| Terrain | Cost (Move Points) |

|---|---|

| Clear | 6 |

| Forest | 9 |

| Hill | 9 |

| Swamp | 9 |

| Mountain | 12 |

| Road | ×⅔* |

| Track | ×1* |

| Sea or River | 6 |

| * This factor is multiplied by the move point cost of the terrain type the road or track traverses. | |

Spending Move Points: On the strategic map, a commander figure moves into a hex, expending the required points. If it hasn’t enough points to move into the next hex, it moves no farther.

Saving Move Points: A commander may save unused points for the following day’s movement. If the unit remains stationary, the points are lost. If a unit halts movement or if it makes enemy contact, excess points are lost.

Note: Saving points for the next day allows movement at ⅔ normal rate, such as through swamp and hills, while avoiding the situation where a figure straddles the line between hexes, which is awkward when we consider enemy contact.

Advanced: Getting Lost

In the advanced game, a small-unit commander, a lieutenant say, may get lost unless following a road, track, or water course. Commanders of larger units do not get lost under normal circumstances.

Forest and Swamp

Only infantry can move in formation through forest or swamp without a road. Ellriendi elves move at Clear rate through their home forest. Lizard men move at Clear rate through swamp hexes.

Mountains

Mountainous terrain is crossable by formed bodies of troops only by road (two parallel lines on the map) or track (line of crosses).

Units, Formed and Unformed

To cross certain terrain, a force may move unformed.1 Thereby cavalry moves off-road through forests, and armies cross mountains. At the end of unformed movement, at a rally point, one day must be spent to reform the troops.

Furthermore, 5 to 15% (half-dice2 × 5, round up to nearest figure) of the force will be lost to stragglers per day of unformed movement. A unit at the rally point may wait for stragglers to catch up (half-dice × 5 per day). On departure from the rally point, any remaining stragglers are lost.

In case of enemy contact, units of an unformed force begin the engagement in a non-rallied state as if in retreat. Though their backs may or may not be to the enemy, each unit rallies at the end of the first turn of mass combat, unless it is attacked. See Retreat and Rout and Continued Retreat or Rout (Chainmail, 16).

Sea

Coastal Waters

Longships and galleys must remain within coastal waters, which extend out to two sea hexes from a coast hex. That is, the vessel can have no more than one sea hex between its current hex and a coast hex.

The north coast from East Port westward is a mud flat at all but times of high tide. Therefore, all vessels must use a channel (marked on the map as dashed lines).

Longships, galleys, and sailing ships may move through coast hexes to another coast hex or to a sea hex. Troop transports may only move into a coast hex that contains a channel or a port.3

Longships and galleys may beach on any coast hex. Sailing ships do not beach but must anchor offshore; troops debark by rowboat. A troop transport requires a port for docking.

Open Sea

Only sailing ships and troop transports may enter hexes beyond coastal waters. Troop transports straying into open sea lose any galley escort. Ships at this distance from the coast cannot see it. Nor can any shoreline observer see ships so far out.

Rivers

Navigating

Only river boats and longships may navigate rivers. All rivers shown on the strategic map, save one, are navigable. The northeast river is a canal last used by the Greater Ones. Now in disrepair, it falls at three points through cataracts (shown as crossing bars).

River boats and longships may beach on either side of any river hex.

Advanced: Upstream, Downstream

A vessel might move upstream at a slower rate and downstream faster. For example, a river boat might have 30 move points upstream and 42 down.

Advanced: Tide

In complex rules, where we track the tide, a vessel might take advantage of the incoming tide to move faster at a river mouth. Moving with the tide, the move cost is halved, against the tide doubled. Tidal reach varies by river. Though six or 12 miles from the sea is usual, up to 60 miles is possible.

Advanced: River Sailing

Longships and small sailed craft (like sailing boats but not sailing ships) might travel along river ways under sail. Rules for wind are required, however, as it is less frequent, and the river’s navigable channel must be wide enough to allow room for tacking against it.

Crossing

The portion of a river, on the map, where opposite shores are separated by white space is considered major river. Where the river is represented by a single line it is a minor river.

Any move cost to cross a river is in addition to that required to move into the hex. For example, infantry (12 daily move points), moving one morning into a clear terrain hex with a minor river crossing their path at a ford, spends 6 move points into the hex and 6 more points to ford the river. The unit makes camp on the opposite shore.

A force crossing a river by any means other than a bridge is considered unformed. The times required for the crossing below include reforming the troops.

Bridges: All arms may cross bridges at full speed—no extra move point cost. Bridges are marked by an arc over the river.

Ferries: Move cost for ferry crossings depends on the river category, described below. Ferries are marked by two dots, one either side of the river.

Fords: As these are navigable rivers, any ford is at least three feet deep but not more than four. These are sensitive to rainy periods. (A later article covers the effects of weather.) Move cost to ford a river depends on its category, described below. Fords are marked by two carets, one either side of the river, pointing to the ford.

Major Rivers

To cross a major river without bridge or ferry, a unit’s only recourse is to build rafts. Collecting timber, building rafts, and crossing require three full days—one day per activity. During the first two days—collecting timber and building rafts—the force is considered formed, but if attacked defends with only one-third its force. In any other than forest or swamp, throw a dice at the end of the first day. A roll of 1-4 reveals insufficient timber. The unit, having lost one day, cannot cross in this hex. Attempt to collect timber in the elven forest at your peril.

Ferries: All arms cross a major river by ferry in two days.

Minor Rivers

Cavalry may cross a minor river without bridge, ford, or ferry, consuming 50% of its daily move points. Infantry may build rafts as in crossing a major river above.

Ferries: All arms cross a minor river by ferry in one day.

Fords: Cavalry crosses a ford on a minor river at full speed, while infantry uses 50% its daily move points.

Advanced: Engineers

Bath mentions a “bridging train” that allows major river crossings (66). In the advanced game, engineer trains might perform other tasks as well, including building bridges, siege engines (also mentioned, 66), and roads.

Notes

1 Rules for unformed units are properly part of a more complex game. In the present scenario, I want orcs and gnolls to be able to travel through mountains, so I include these rules. Still, as the disadvantages are great, a commander is advised to choose routes where units may move in formation.

2 A half-dice is the result of a dice throw divided by two rounded up.

3 Troop transports, converted from large sailing ships, may not hug coastlines due to a 10-foot draft.