Beyond the Pale

This is the last in a series of nine articles, which outlines a D&D campaign. This is a broad overview. Many details are left for the DM to fill in according to his or her own inspiration.

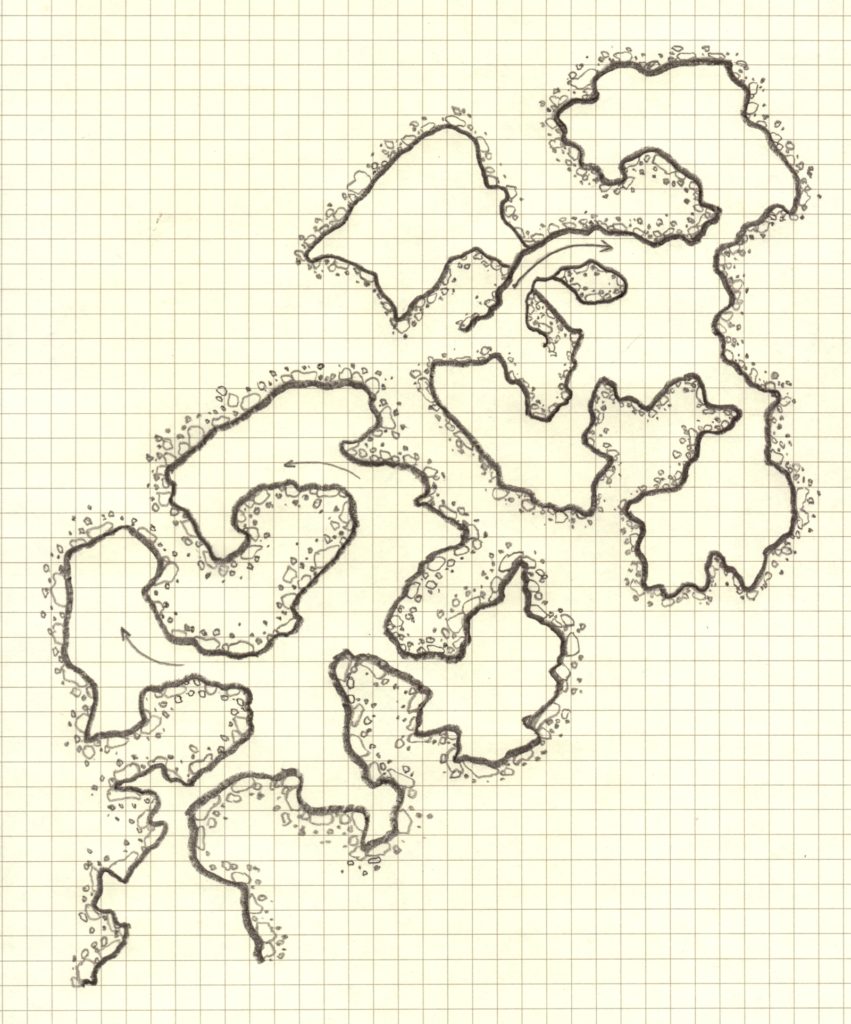

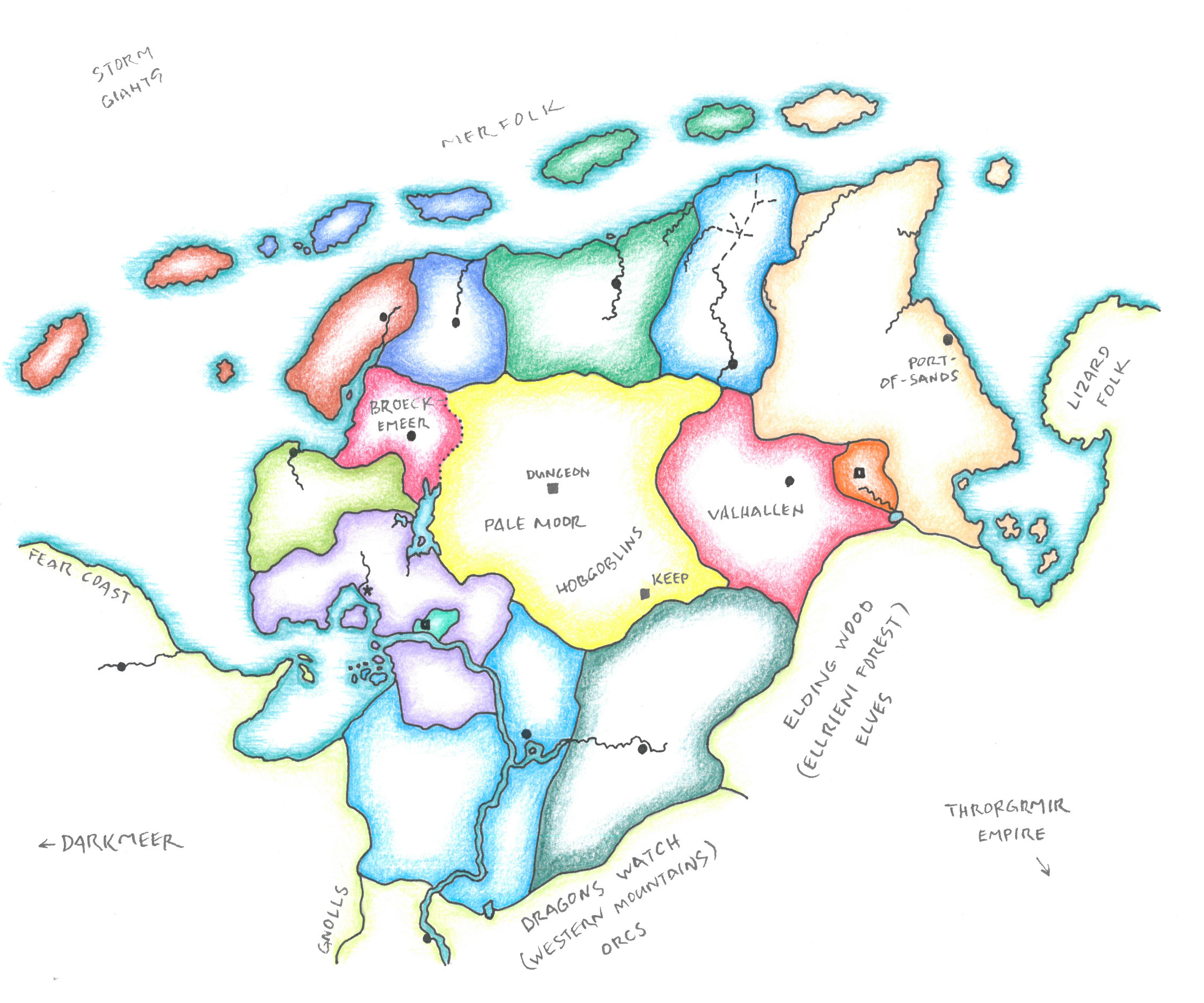

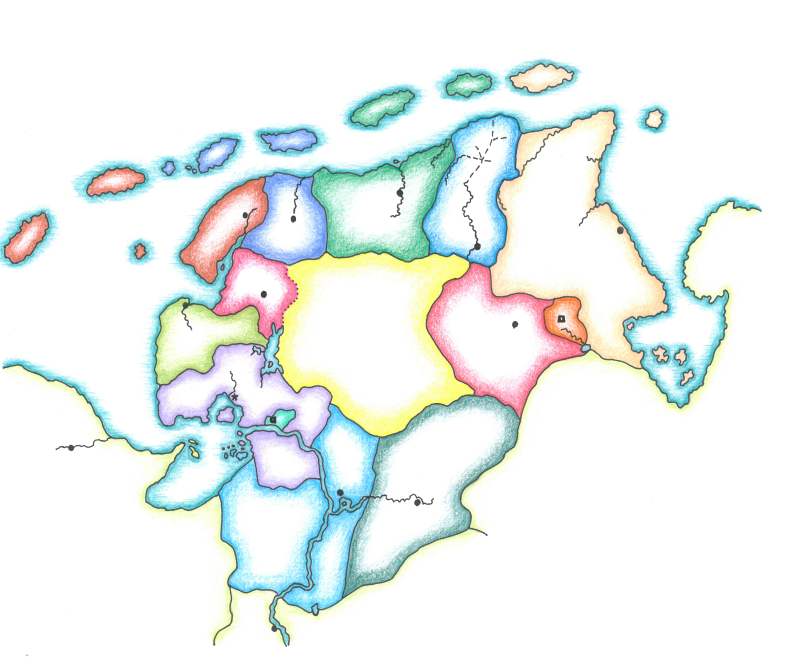

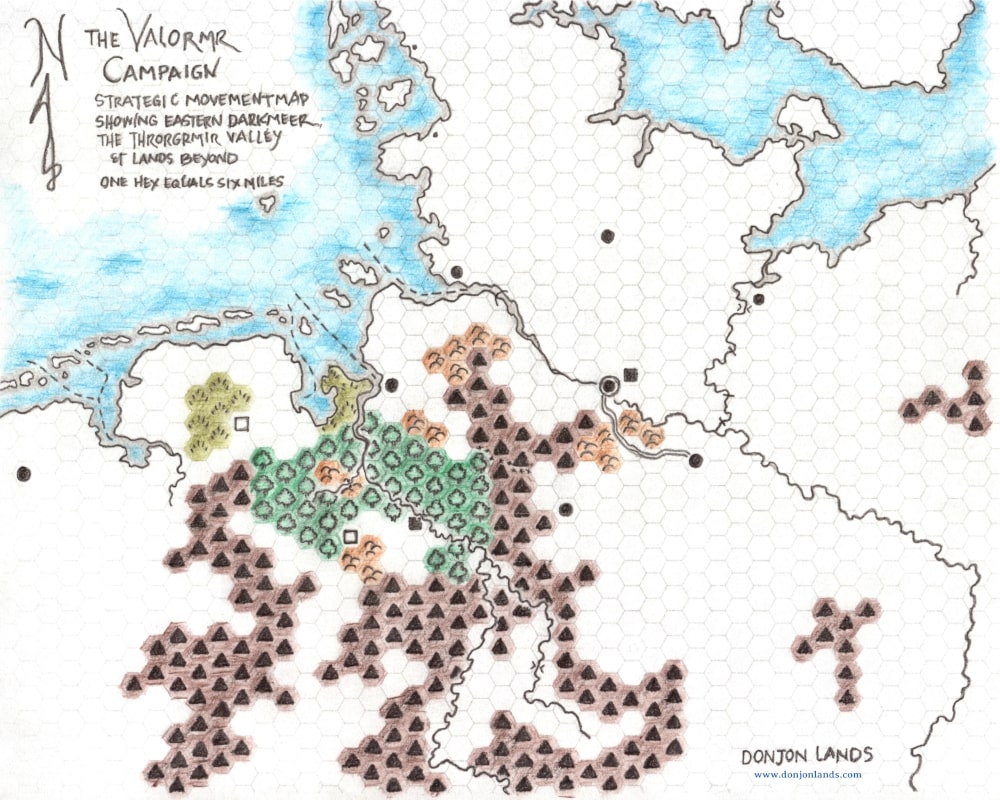

Here we cover the campaign background, generally known throughout the Hex Lands, in addition to local rumors that might be collected by adventurers. I’m working on a more elaborate campaign area map.

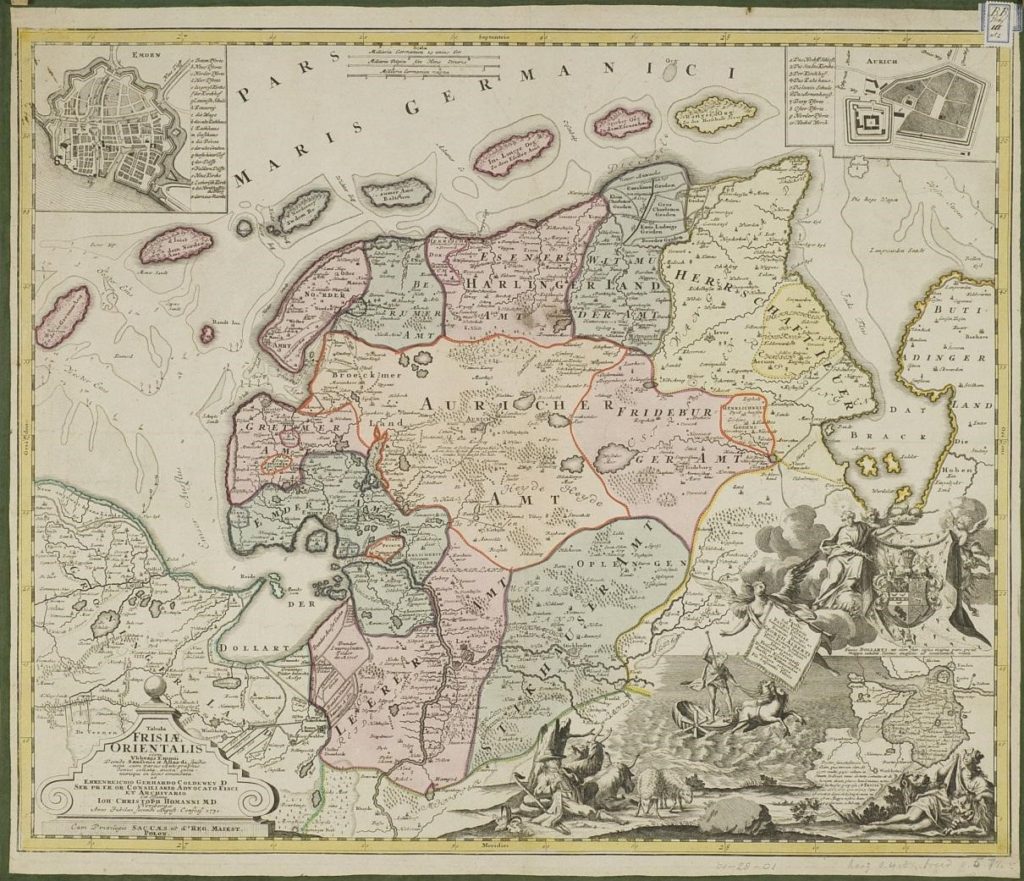

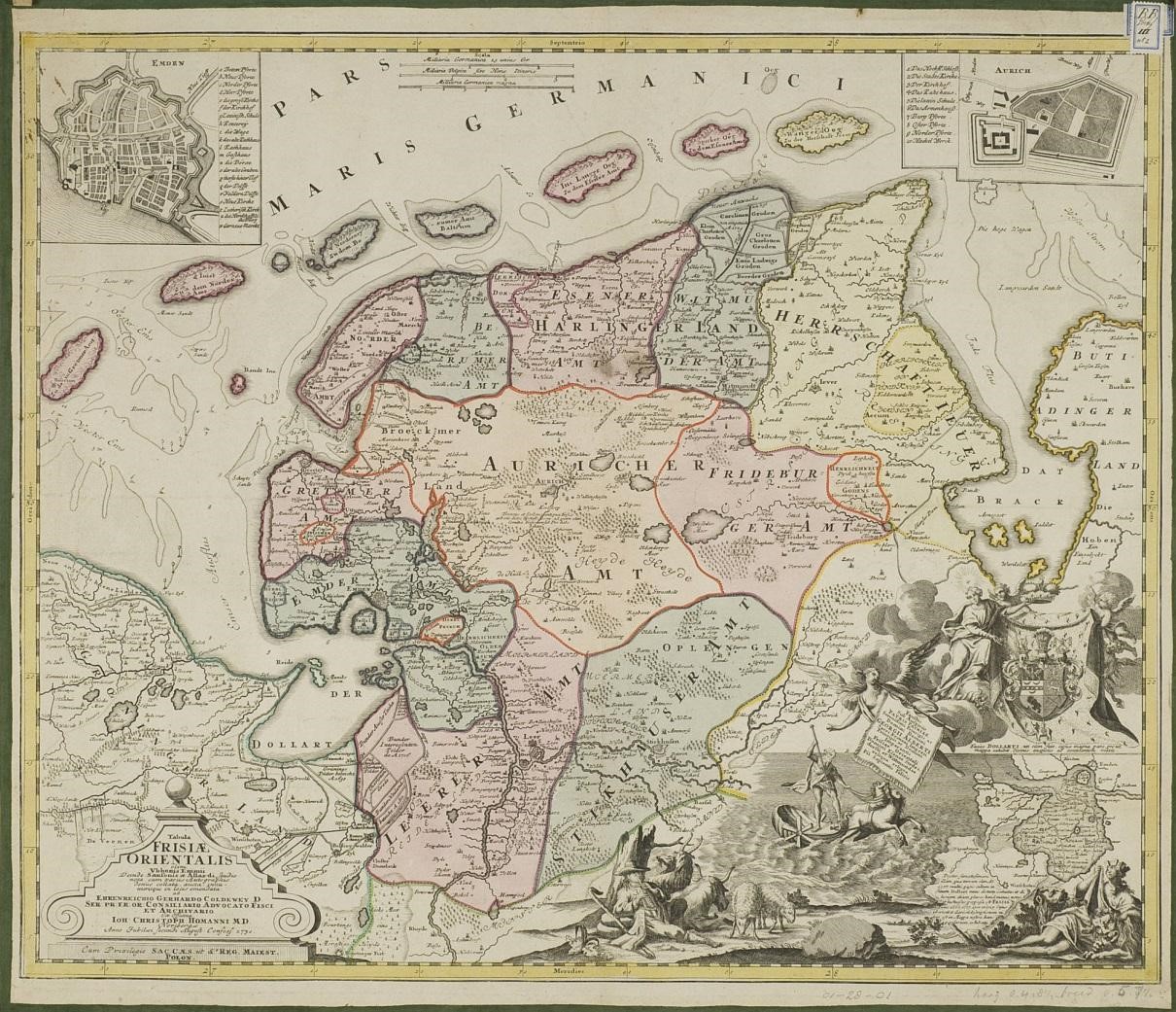

Beyond the Pale is a B/X D&D campaign inspired by an old map.

Background

Troglodytes once thrived in this lowland peninsula. Their former cave homes riddle any sedimentary rock that protrudes from the spongy bogs and shallow meres of what has been known throughout living memory as the Forsaken Peninsula.

Troglodyte legends tell of demons that sometimes ravage the land and devils that pursue devious plots. Fireside tales recount meetings with such infernal beings. These legends and rumors bring witches and warlocks to the region, seeking to practice their black arts under the tutelage of a damnable mentor.

When the Chaos Armies invaded the Throrgrmir Valley, they built a fortress on a promontory rock in the interior. The keep served as staging area and supply point for the armies that marched from Darkmeer in the west to take the dwarven citadel in the southeast. Supplies came by land from the west and from the east by sea through Port-of-Sands, which was also held by the Chaos Armies.

As the war progressed, the Forces of Law took the port and stormed the keep, cutting the enemy supply line. When Port-of-Sands was taken, a warlock who accompanied the garrison withdrew to the keep. When the keep fell, the warlock fled to the peninsula’s interior.

The Chaos Armies, denied reinforcements, were weakened but still held the citadel. Weeks of hard fighting brought the Forces of Law to the citadel’s gate and victory at the Battle of Throrgrmir.

After the war, the Throrgrmir dwarves desired to set up a buffer state between their prosperous valley and the evil denizens in Darkmeer. To draw settlers, they offered a favorable trade agreement with any who would settle the peninsula. Settlers came, and thirteen counties, called graves, were established.

In the interior, meanwhile, the warlock discovered the remains of an ancient city. Though in crumbling ruins, it contained much wealth and magic. When word spread, many adventurers came to claim the wealth, but the warlock repelled them with black magic.

The warlock enclosed the ruins inside a thick wall and built a great tower as a stronghold and base of explorations. The adventurers raised bands of mercenaries to rout out the warlock. They were defeated by an undead army. The vanquished—adventurers and mercenaries, slain and captured—all were impaled. Tall stakes bearing corpses were posted around the interior’s perimeter. Soon after, a curse was laid upon the Pale Moor: any who die within the interior rise again in undeath.

The incursions ceased. Though the curse denuded the stakes, the gruesome palisade yet remained. The perimeter came to be called the Pale, and the interior the Pale Moor.

Some four centuries have passed since the Battle of Throrgrmir. The dwarven civilization, now confronted with a primordial wyrm and its wyrmling spawn, is in decline. As their eastern ally weakens, the Thirteen Graves are threatened by the petty fiefs of Darkmeer.

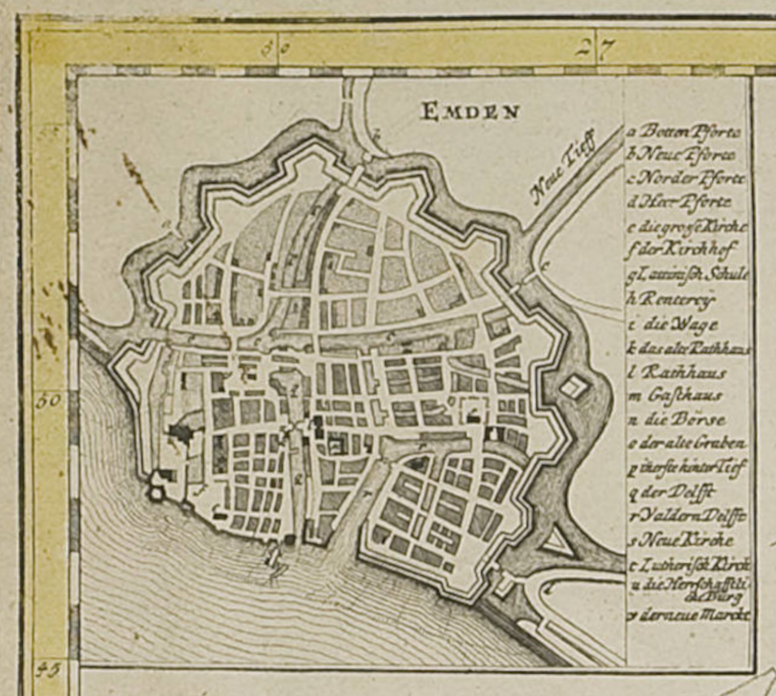

The strongest of the graves is Emder. Recently, the landgravine united eleven of the Thirteen Graves in an alliance against their common enemy to the west. The remaining two graves, Broeckemeer and Valhallan, abstained from the alliance.

The point of contention is the Pale Moor. Under the terms of the alliance, the interior and its resources are to remain unclaimed. Broeckemeer claims the Pale Moor as part of its domain. Valhallan is known to sponsor forays into the interior.

The alliance further strengthened its position by forming a duchy and promoting Emder’s landgravine to herzogin. Two of the eleven graves, though they still participate in the alliance, refused to swear fealty to the herzogin, preferring to remain independent.

On the Pale Moor, the baleful curse prevents incursion. A few dwindling troglodyte tribes, pushed out of the coastal regions, eek out an existence within the perimeter. Goblinoids sometimes cross the Pale to raid towns and villages. The disused keep long ago fell into ruin. Its location is now lost.

The Pale

pale noun

(Entry 3 of 5)

2 b : a territory or district within certain bounds or under a particular jurisdiction

3 a : one of the stakes of a palisade

impale verb

1 a : to pierce with or as if with something pointed

especially : to torture or kill by fixing on a sharp stake

Rumors

I love a rumor table. These are general entries drawn from information provided in the series. A DM should add rumors as he or she further fills out the setting. Most should apply to the opening adventure. A table of 12 is good enough to start, 20 is best. Taking a cue from Dungeon Module B2: The Keep on the Borderlands, about one-third should be false.

In addition to the background above, a player character may have heard one of the following rumors. Those marked with an f are false.

- The warlock retrieved a powerful artifact from the ruins of the ancient city.

- f The ancient city was built by demons and razed by an infernal army.

- Broeckemeer’s ruling family consorts with demons.

- The warlock’s tower is built on the foundation of a donjon of the Greater Ones.

- f The Keep on the Pale Moor was consumed in a great conflagration that burned for thirteen days and nights.

- f The Allfather released a great flood three centuries ago upon the Reidermark, whose populace worshiped devils.

- The herzogin sponsors worthy adventurers to make expeditions beyond the Pale.