Advanced Combat

This is the 16th in a continuing series of articles, which reedits house rules for Holmes Basic D&D from 40-year-old game club newsletters. Mentions of house rules are in bold text and followed by a [bracketed category designator].

For rules category descriptions and more about the newsletters, see “About the Reedition of Phenster’s.” For an index of articles, see Coming Up in “Pandemonium Society House Rules.”

Phenster’s Pandemonium Society House Rules is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, events, incidents, and newsletters are either products of the author’s imagination or are used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is pure coincidence.

Losing Balance

In the excerpt on critical misses from “Combat Complications” (L’avant garde #49, September 1982), Phenster refers to losing one’s balance in melee. In “Advanced Combat,” three months later, he adds:

Sometimes, especially whenever we're fighting on rough terrain, when we lose our balance there's a chance we might fall down. We have to roll our dex score or less on a d20. Rough terrain is like a field of rubble, a steep slope, or a dungeon floor where stone blocks have been upset by an earthquake or tree roots growing under them. We can't fight from the floor (+4 AC), and it usually takes a turn to get up.

—from “Advanced Combat,” L’avant garde #51 (December 1982)

As “off balance” appears twice in Phenster’s list of possible results due to a critical miss, when using the rule Critical Miss: Lose Next Action [E], consider Balance [P] as a supplement. I put it in the [P] Pandemonium category, because it adds a dice roll to the end of what should be a quick resolution of a combat action. Another option is for the DM to adjudicate, including the fall (or not) in the critical miss result.

Balance [P]

A character who loses balance on uneven ground (e.g. rough or sloping terrain, stair steps) must make a Dexterity check or fall prone.

Prone [E]

A prone character cannot attack, and any attacks on the prone character are made at +4 on the dice. A prone character can stand in one round.

Drawing a Weapon in Melee

“It takes one melee round to draw a new weapon, but one hanging free, or in the other hand, can be employed immediately” (Holmes 21).

According to the rules you can draw a weapon in one round. You can usually only do one thing at a time, but we say you can also draw a weapon while you move, like when we're closing to melee.

—“Advanced Combat”

Draw Weapon While Moving [E]

A combatant may draw a weapon while moving.

Charging and Other Movement in Combat

In the following excerpt, end 1982, Phenster refers to “fully armored” characters, which I assume he gets from Holmes’s Movement Table (9). In Charge [E] below, I translate to any armor, because in 1984 Phenster adds move rates for characters wearing leather armor: In L’avant garde #63 (May 1984), he places “half armored” characters between unarmored and fully armored on the movement table. He also halves the move rates given on the Holmes table.

Phenster does not specify whether a half armored character gets the damage bonus for charging. I defer to Chainmail, which gives the impetus bonus to heavy and armored footmen (17).

Besides Charge [E] and Half Armored Move Rates [E], Maneuver [E] allows a step in melee.

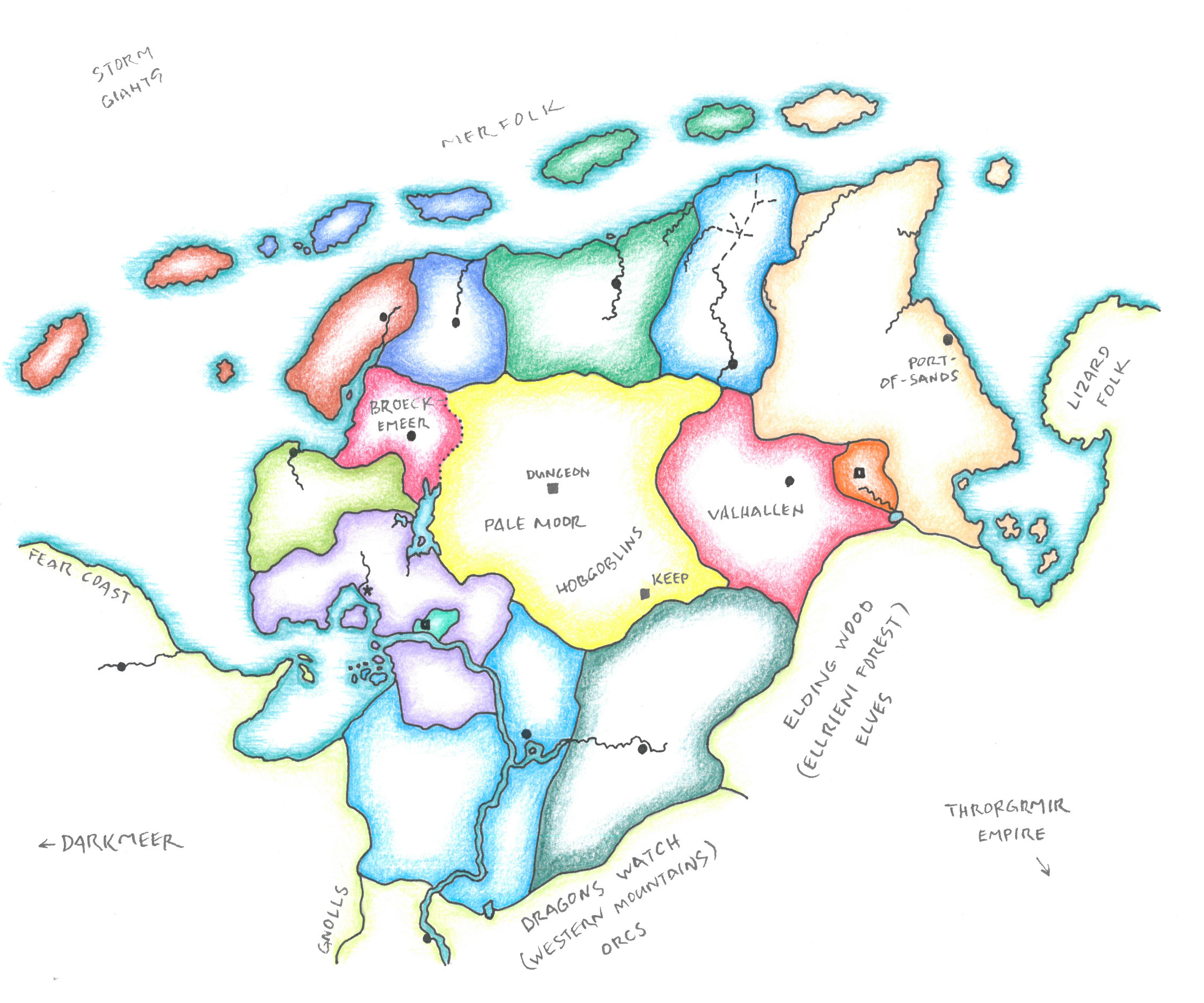

If you are not more than THREE TIMES your melee move distance away from your opponent, you can charge. But it has to be over flat/level ground without any obstacles, and the opponent has to be at least 10' away. If you hit and you are fully armored, you get a +2 bonus on damage from the impetus. And if you slay your opponent, your charge continues and you can attack again if you charge into another opponent, until the end of your charge. Your charge has to be in a straight line.

—“Advanced Combat”

Charge [E]

When an opponent is at least 10' and not more than thrice combat move distance away, a combatant may charge the opponent in a straight line over level terrain. If the attacker is wearing armor, a charge grants a +2 bonus to damage. If the opponent is slain, the attacker continues the charge up to three times combat move distance, engaging subsequent opponents.

Whereas contemporary D&D editions apply the charge bonus to the attack roll, Phenster applies it to damage. One interpretation of Chainmail’s “Impetus Bonus” (17) would do likewise.

Half Armored Move Rates [E]

Characters wearing leather armor or equivalent move normally at 180 feet per turn. They move at 90 feet per turn while exploring, and 15 feet in a combat round.

Flank and Rear Attacks

If you can attack from a monster's flank (90 degrees from its front), you get +1 on the attack. If you come up behind it, you get +2. You're supposed to add another bonus if the monster has a shield and can't use it (like if you're on its right side), but Hazard doesn't mess with that. He just says attacks from behind get +2 on the roll.

You DO NOT get the bonus for flanking if you're less than 90 degrees from the front. If the monster's fighting somebody else and you come up beside it, you might only get one attack with a bonus before it turns to put both its enemies at 45 degrees to its front.

—from “Combat Complications,” L’avant garde #49 (September 1982)

Flank and Rear Attacks [E]

An attack from a flank gains a +1 bonus on the dice; from the rear, +2. Whether the defender wields a shield or no is not considered. Assume that a combatant can change facing (left, right, or about face) on its count in the initiative order or any time immediately prior to an attack.

Defend in Place

Jinx had a good attack roll for once, and he hit the grimpshee with his sword but didn't do any damage. That's how we knew it was immune to normal weapons. So Jinx stepped to one side of the door and defended in place (-4 AC), while Friar Tombs came up with his snake staff, and Phenster Prime threw protection/evil 10'.

—from “At the Gates of Pandemonium,” Paradigm Lost #4 (December 1982)

Full Defense [E]

A melee combatant may forego all attacks and other actions to devote the round to defense, thereby gaining a −4 bonus to armor class. When so defending, only a step is allowed in the round (see Maneuver [E]).

Fighters vs Humanoids

. . . Orcs everywhere—we were surrounded! Mandykin fired her crossbow then drew a sword. I didn't have any spells left, so I took out my dagger to defend my skin. Friar Tombs struck one with his mace. Then it was the Bully's turn. He swung his two-handed sword once and two orcs fell. He swung again and another one went down. Five more swings and all the orcs were dead or ran away. He got so many attacks because he's a 7th-level fighter. If it was 2 HD monsters, like gnolls or lizard men, then it would be 3 attacks.

—“Advanced Combat”

Fighter Multiple Attacks vs Humanoids [E]

Fighters get multiple attacks per round against humanoids. Divide the fighter’s level by the humanoid’s hit dice, drop any fraction. Treat less than 1 HD monsters as 1 HD, and ignore any bonuses to base hit dice. The fighter makes all attacks at once in the usual order of attacks.

Fighter Damage Splatter vs Humanoids [P]

When a fighter slays an undamaged humanoid with one attack, any extra damage is taken by another humanoid, if it is within the fighter’s reach and would be hit by the same attack roll. If the second humanoid was also undamaged and is slain, any remaining damage is taken by another humanoid meeting the same conditions, and so on.

Because it implies the fighter swipes through multiple enemies with a single swing, this rule, for me, feels over-the-top, so I throw it in the [P] Pandemonium category. It can, however, speed up those big combats, and it makes the fighter player feel good.

Hireling and Monster Reactions in Melee

It didn't make any sense that the PCs can decide to run away when the monsters are too tough, but the monsters don't run away when it's plain they're going to be slaughtered. Our NPCs might lose their nerve too, and they might run. Hazard mostly just decides for the monsters and NPCs when their going gets tough. But when he isn't sure, he uses the Hostile/Friendly table from the rulebook to see if the monsters will cut their losses and run. He gives the monsters a number depending on how brave they are. Most monsters fall into the 6 to 8 range. Hired NPCs usually get a 7. For example, kobolds have an 8 morale (Normally courageous), ogres have a 5 (Sturdy), and dragons have a 3. And Clare Brighthelm, a Knight of the Celestial Hart, is Stalwart; she never backs down from a fight.

2: Stalwart, never runs away, never surrenders

3-5: Sturdy, fierce, battle-hardened

6-8: Normally courageous

9-11: Weak of will

12: Coward, always runs away

Whenever the monsters could have a second thought about going on with the fight, Hazard rolls two d6s. If he rolls below the number, the monsters run (or give up if they can't escape). But if he rolls the number or higher, they fight on.

—“Advanced Combat”

Morale [E]

The DM assigns a moral score based on his or her judgment and interpretation of the creature crossed with Phenster’s table. Hirelings begin with a morale score of 7. On a 2d6-roll result lower than the moral score, the creatures flee or surrender. When to check morale is also left to the DM’s discretion.

DMs who find Hazard’s system too haphazard may consult B/X (Moldvay, Cook, Marsh, 1981) for a similar system more fully detailed.